Using technology to improve communication in panels

Authors:

Jonathan Grudin

Posted: Fri, September 30, 2022 - 11:34:03

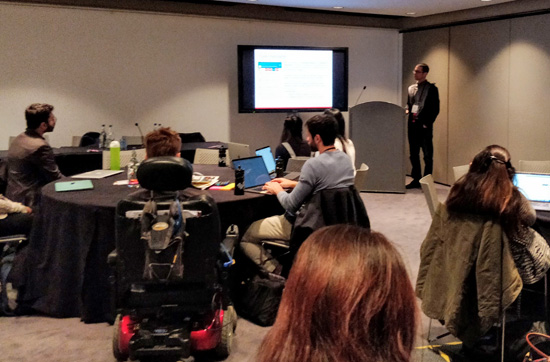

Panels can be fun to develop—they can also be much more effectively executed. This spring I was on two large panels that were the best organized of any I’ve participated in. Technology was used in advance to reduce psychological uncertainties, which increased interaction and kept us focused on our message. Expectations were exceeded. Both of the panels were in person, but the method is even more promising for hybrid panels.

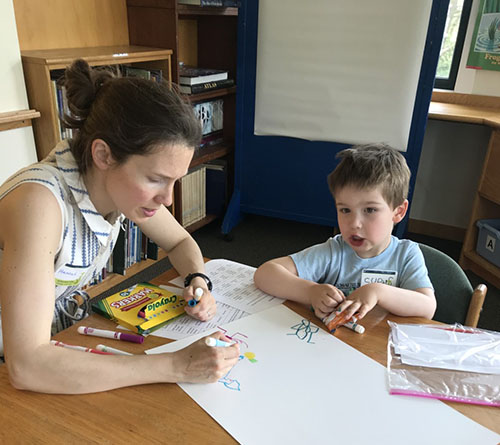

The first panel was organized by SIGCHI Adjunct Chair for Partnerships Susan Dray and VP of Finance Andrew Kun to discuss CHI’s 40th anniversary. Structure that one might assume would squeeze out liveliness instead promoted it. Impressed by its success, I reprised the method in another 90-minute panel at my Reed College class reunion. These are only two data points, but the underlying psychology is compelling, especially for large panels and future hybrid panels.

The 40th anniversary panel was an exceptionally diverse group of eight, plus Andrew as moderator. Our backgrounds, interests, and priorities differed substantially. Forty years earlier, one of us wasn’t yet in school and only one was involved with CHI. Yet we wanted to avoid eight 10-minute talks—we wanted to engage with one another.

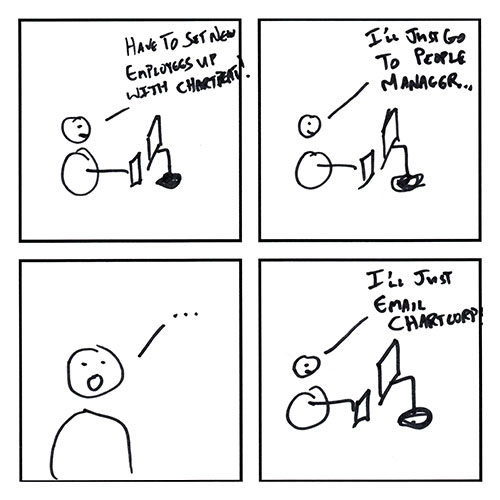

Andrew’s solution was to address psychological barriers to effective time management that I had never noticed. Panelists like to talk. The trick: Make it possible for panelists to avoid saying more than they really want to.

A large panel should minimize moderator control onstage to give panelists time to get their points across, but if panelists are undirected, meandering and a lack of coherence are inevitable. Andrew directed the panel, but he did so in advance, which greatly reduced the cognitive effort required of panelists at the event.

Before the event

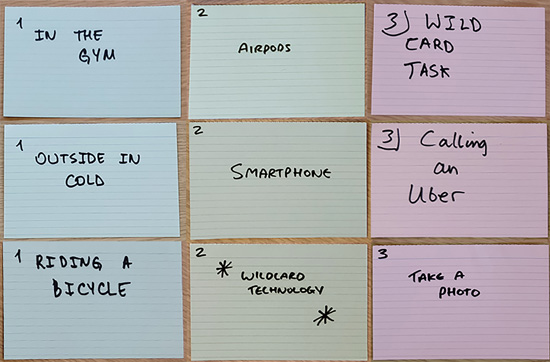

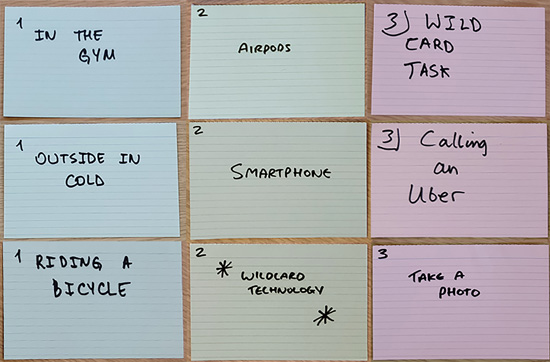

Weeks in advance, Andrew shared a Google Doc that asked panelists to draft text for four sections:

- A bio

- A two-minute opening statement or “provocation”

- One or two questions from each of us directed to another panelist (encouraged to ensure that each panelist was asked at least one question)

- A one-minute concluding summary.

Two virtual meeting deadlines ensured that we completed drafts in a timely fashion. Everything could be revised up to the event, but Andrew could also sequence opening statements early to create a coherent topic flow. Seeing one another’s drafts and the presentation sequence enabled us to keep statements to the same length, reduce redundancy, share terminology, and shape questions and summaries.

Seeing a question that would come our way in advance, we could organize a response, but responses were not shared. They were fresh to other panelists at the event, and anyone could contribute thoughts if the initial respondent didn’t cover them.

At the event

We had crafted crisp bios that Andrew read to introduce us. Our opening statements were practiced, fluent, and within the allotted two minutes.

The key innovation was the handling of the Q&A. Andrew had carefully thought through the questions and prepared a sequence of invitations. For example, “Daria, do you have a question for another panelist?”

The crucial point: We knew that Andrew was always ready to solicit the next question. Think of your experiences on a panel. Panelists are often unsure about the best way to continue and keep the discussion going. This leads to fuzziness or discontinuities. Three scenarios:

- I ask a question and receive a satisfactory response. If I have nothing to add, I’m in a bind. Not knowing whether someone else will jump in if I stay silent, I often politely respond or ask an unnecessary follow-up question to keep the conversation going. In our event, I could pause and glance at Andrew. If no one immediately spoke, he moved on: “Tamara, do you have a question for another panelist?”

- There is a pause in the discussion. Has the current topic been covered adequately? I haven’t spoken yet, Should I break the silence, even if what I will add is mostly to agree or digress? At our event, there was no pressure to do this. Andrew was ready to break the silence and move on to the next cogent question.

- A topic is exhausted. It’s clearly time to move on. I have a very different topic, but someone else may have a more relevant continuation. Should I jump in? In our panel, we could leave graceful transitions to Andrew, knowing that our question would get its turn. Andrew was following the discussion and knew the range of questions remaining.

I felt that a cognitive load had been lifted—it was great! The navigation of conversational conventions adds many small efforts that compete with focusing on what is said and the overall topic. There were no space-filler comments as we engaged with one another.

I’d initially thought that although structure might be necessary for an eight-person panel, it would sound scripted and diminish spontaneity. That wasn’t the case. We added follow-up questions and comments after one of us responded. The conversation was brisk and focused on things we cared about. Little cognitive work was required for conversation management.

A replication

For my 50th college reunion six weeks later in Portland, Oregon, five people who spent careers in tech formed a panel to discuss how tech had evolved, our roles, and what we recommend younger people think about. I introduced Andrew’s structure. With five panelists, we doubled time allowances and mixed our prepared questions with less predictable audience participation. It went well. People go to college reunions more to hang out and socialize than to attend lectures and panels, but we drew a large crowd who stayed throughout.

Natural for hybrid panels

Efficient conversation management is critical for large panels. This approach also offers benefits for virtual or hybrid panels. Hybrid planning is by necessity online—which means there’s no opportunity to get together for breakfast the day before—so coauthoring a structured document and holding a couple of preliminary meetings is a natural fit. More significantly, navigating conversation transitions is more challenging when panelists have less awareness of one another’s body language. Hybrid panels may gravitate toward larger sizes, and cultural diversity could require bridging conversation styles.

This structure requires more preparation, but it was distributed over time, getting a better sense of other panelists’ contributions reduced some of the effort, and the collaboration was enjoyable. It was worth it.

Posted in:

on Fri, September 30, 2022 - 11:34:03

Jonathan Grudin

Jonathan Grudin has been active in CHI and CSCW since each was founded. He has written about the history of HCI and challenges inherent in the field’s trajectory, the focus of a course given at CHI 2022. He is a member of the CHI Academy and an ACM Fellow.

[email protected]

View All Jonathan Grudin's Posts

An American Zen Buddhist’s reflections on HCI research and design for faith-based communities

Authors:

Cori Faklaris

Posted: Tue, August 16, 2022 - 4:29:20

Computer science seems in opposition to Zen Buddhism, a spiritual practice best described (if it must be) as “without reliance on words or letters, directly pointing to the heart of humanity” [1]. Yet with so much of today’s human experience bound up in computing, some words, and pixels and bits, to address their overlap seem necessary. My aim in sharing the following reflections is to set forth the historical and modern faith context for a secular wellness practice that we design for— meditation—and to model the statements of positionality and reflexivity that I feel are essential for research in such personal and cultural domains.

Zen Buddhism

Zen’s origins were first documented during China’s Tang dynasty in the 7th century CE. At that time, Buddhism had already spread from Nepal, the birthplace of historical founder Siddhartha Gautama, or “the Buddha,” throughout neighboring countries in Asia for more than 1,000 years. The Indian monk Bodhidharma is credited with introducing China to the dhyana practice of stillness and contemplation. Dhyana (a Sanskrit word) predates the Buddha and is commonly described as his vehicle for achieving enlightenment, or the transcendence of his limited human existence. The renewed focus on dhyana was a reaction to the older branch of Buddhism known as Theravada, the “way of the fathers” [1]. The chief text of the newer Mahayana branch of Buddhism is the Heart Sutra, the English translation of which fits on one page. Zen takes this minimalist approach even further, proclaiming the superiority of empirical knowledge gained through dhyana —renamed ch’an in Middle Chinese—over scriptural learning or formal religious observance. A famous poem of the Tang dynasty sets forth this formulation for Zen [1]:

A special transmission outside the scriptures

Without reliance on words or letters

Directly pointing to the heart of humanity

Seeing into one's own nature.

Today, the largest Zen communities remain in China and Japan (the origin of the word zen), but the practice of Zen has spread throughout the world. Like other Buddhists, who number in total 488 million worldwide [2], they venerate the “Triple Treasure” of small-b buddha (inherent enlightenment-nature), dharma (the teachings and practices), and sangha (their faith communities). Zen practitioners also particularly value upaya, or “skillful means” (the ability of an enlightened being to tailor a teaching to a particular audience or student for maximum effectiveness) and mindfulness (in Zen, the continuous, clear awareness of the totality of the present moment). Through seated meditation, alternated with practices such as chanting, bowing, and contemplative walking, a Zen Buddhist aspires to a state of mindfulness that will facilitate their own perception of buddha-nature and help them express this enlightenment in daily life, especially for the benefit of others. To check the validity of their meditation experiences, Zen practitioners are urged to consult with a teacher in an established lineage who is certified to guide others in enlightenment. Among a teacher’s “skillful means” are stories or riddles known as koans (Japanese), gong-ans (Chinese), or kung-ans (Korean). Such consultations will help Zen practitioners achieve a “before-thinking,” other-centered orientation and avoid self-centered fallacies—for example, “wanting enlightenment is a big mistake” [1].

Personal experiences and observations

My own experiences with Zen are Western. I began in my teenage years, when I bought a secondhand copy of D.T. Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism and was intrigued by his discussions of satori, the Japanese word for enlightenment. I had already liked what I had heard about Buddhism during a unit on world religions at my (Catholic) grade school. However, it wasn’t until I moved to the U.S. state of Indiana that I was able to connect with an in-person group, practicing in the Kwan Um School of Zen (KUSZ) in the lineage of Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn. I began sitting with the Indianapolis Zen Center sangha once or twice a month as my schedule permitted: 30 minutes of seated meditation bookended by a 20-minute prelude of chanting and a 10-minute epilogue of a reading and announcements. I progressed to sitting weekend retreats and to taking precepts (like Christian baptism, this signifies formally joining the faith). Eventually, I studied for and became a KUSZ dharma teacher—qualified to explain subjects such as meditation forms and the history of Zen, but not to guide people to enlightenment. In KUSZ, such teachers are called Ji Do Poep Sa Nim (JDPSN, for "dharma master") or Soen Sa Nim (Zen master). I have studied with both types of “enlightenment” teachers at the Indianapolis Zen Center and with a group in Pittsburgh, PA, while helping as a dharma teacher.

As a Zen teacher, I do not take a binary view of computing as good/not good or useful/not useful. The “middle way” is to acknowledge that it is a dharma aid in some contexts and a distraction in others. Below are some examples.

Computing as obstacle to Zen practice

My advice to beginners is to turn off their smartphones completely. This is because a buzz or ding is liable to take meditators out of the moment, and beginners often will struggle to refocus. For my in-person group, I model another best practice by taking out my phone or smartwatch, silencing them, and turning them face-down on my meditation cushion, so that I cannot see the flash of a notification. I prefer to use such manual safeguards for attention rather than the “Do Not Disturb” settings, because enacting the exercise of putting away our digital helpers is an important signal to our bodies and minds that what we are doing is important and different from the everyday flow of our distracted lives. In the same vein, I recommend use of a battery-operated analog clock over a smart device for timing seated meditation, because it will not tempt you into checking messages.

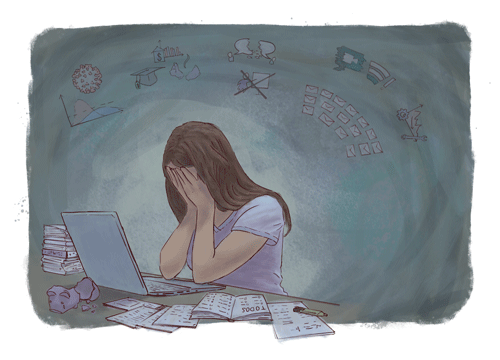

In the world of Covid-19, much of our group Zen practice has joined others online. Now, it is no longer possible to physically remove ourselves from our Internet-connected devices. I am grateful to be able to see and hear my fellow practitioners even at a distance, but I miss having the break from my busy digital life and from the allure of its distractions. The “Do Not Disturb” settings help, to a point. Sitting in front of my MacBook, however, I catch myself touching my mouse and calling up screens whenever I experience a fleeting thought about, say, the status of a project. Meditating from home also means interruptions from family members, pets, or Internet outages. I confess that I do not have enough “dharma energy” to avoid breaking my stillness in response to my cat waving her tail in my face!

Going forward, this type of Zen Buddhism will benefit from computing research and design to solve similar problems of distraction and focus as those faced by those working from home or who are “digital nomads,” connecting to their customers or clients via the Internet away from an office. I would love to flip a switch inside my home environment and be free from all ability to access Netflix or Slack while I hunker down on either a research paper or a kung-an. Even better if the “switch” is a timer, so that I do not forget to turn off my “Do Not Disturb,” or a learned routine of my home network, so that it is context-aware and picks up on the signals that I am ready to concentrate. I use Siri now to set a meditation timer by voice, although the screen and keyboard is still nearby, and it would be better for my ability to stay in concentration if “she” could turn off everything at the same time and then turn it back on again after the timer ends.

However, like the meditators in Markum and Toyama [3], I am wary of letting technology intrude too far or replace in-person experiences. I am doubtful that it will no longer be necessary to visit a Zen center or monastery for the sustained concentration required for intensive practice. My Pittsburgh group has returned to offering a weekly in-person (and masked) practice so that people can get a break from remote meetings and reap the benefits of in-person group meditation. I look forward to the day when we can begin traveling to other temples and learning in situ about others’ spiritual practices, perhaps with the assistance of interactive displays or augmented reality overlays.

Computing as support to Zen practice

Is reading an obstacle? After all, “words and letters” are considered a hindrance in Zen tradition. However, reading is often the first step undertaken by someone who wants to try meditation and/or to learn more about Zen Buddhism. As Bell has noted [4], the internet has been enormously helpful for spreading Zen knowledge and for connecting seekers with faith communities. My sanghas have made use of the same computing affordances as other interest groups: websites, online groups, platforms for event discovery, and secure no-contact payments.

I will always prefer in-person Zen practice. But, like the online group members in Katie Derthick’s work [5], I now can join a Zen meditation session or a retreat from anywhere in the world. I can take part in a distant reading group or a book club (we have those!). I can receive an interview via video and audio from a variety of Zen teachers. For those who don’t want that group experience, a variety of apps can guide them in contemplating peace or following their breaths. Headspace even dims the screen so that you can use it to wind down and prepare for sleep.

Going forward, the main item on my wish list is better audio support for remote Zen practice. We have experienced glitches in teacher interviews where one person trips over the other person’s statements, adding to the problem of not being present to pick up on nonverbal cues to turn-taking such as angling back or tilting forward. Worse, audio problems have almost killed our group chanting. This is unfortunate because, in my tradition’s Zen practice, chanting is essential for aligning participation and building an energy within the group that supports its focus. Participants cannot stay in sync—the farther from the source, the more obvious the transmission delays. Our Zoom apps also struggle to figure out which voices to prioritize, instead of blending every audio source into a unified output. For now, the workaround is for everyone to mute and only listen to the leader’s chanting. We need apps like JamKazam or Jamulus, which were designed for musicians to play together online and at a distance. Such an app will need to integrate with our existing remote meetings and be usable by anyone.

Suggested best practices for computing researchers

Religion is as sensitive a topic as it is central to the human experience. From my N of 1, I suggest that computing researchers will do themselves good to consider their positionality and biography with regard to this subject, before embarking on faith-minded research [6,7]. Clarification of our personal experiences—how we were raised and how we have directed our adult lives with regard to religion—will make explicit our social, cultural, and historical position with regard to the faith domain. Reflexivity requires time, but reading, discussing, and thinking will help us to identify what assumptions we bring to the project. Once articulated, our preexisting assumptions will be less likely to warp our research or to stymie our openness to new ideas. (In my case, I sat and thought about whether I have a bias toward adding technology to any faith domain, regardless of whether it is truly needed. I also challenged myself as to whether I assume that adding technology will lead to only negative downstream effects for a religious community.)

For the conduct of this research, I suggest three ethical pledges that will reduce the potential for exploiting participants: adherent-centeredness, getting close-up, and considering relationship ethics. Researchers should prioritize the faith population’s needs, preferences, and values, and incorporate them to the extent possible: “Nothing about us, without us.” Careful, respectful qualitative work such as Wyche et al. [8] follow Genevieve Bell’s prescription to use techniques informed by anthropology, focusing on the particulars of place, location, and critical reflexivity [9]. Researchers should make use of practices such as participant observation that foster empathy and consider layering different participants’ accounts, rather than aggregating them into a majority narrative [6]. And they should recognize that such research will involve leveraging existing relationships and fostering new ones. Discuss issues of privacy and confidentiality upfront, for example, that it may not be possible to de-identify anyone [6]. Share work and ask for responses and comments. In publications, alter specific personal or topic details to protect their privacy, security, and safety.

These suggestions may sound like standard operating procedure for some qualitative researchers in human-centered computing. But many of us are trained in a positivist orientation, in which reason and logic are prioritized. We will benefit from having these or similar principles explicitly articulated for our consideration and commitment, just as a Zen master benefits from reciting the temple rules about not borrowing people’s shoes and coats. We all need help staying mindful.

Endnotes

1. Sahn, S. The Compass of Zen. Shambhala Publications, 1997.

2. Buddhists. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. Dec. 18, 2012; https://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-buddhist/

3. Markum, R.B. and Toyama, K. Digital technology, meditative and contemplative practices, and transcendent experiences. Proc. of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2020, 1–14; https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376356

4. Bell, G. Auspicious computing? IEEE Internet Comput. 8, 2 (Mar. 2004), 83–85; https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2004.1273490

5. Derthick, K. Understanding meditation and technology use. CHI ’14 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2014, 2275–2280; https://doi.org/10.1145/2559206.2581368

6. Darwin Holmes, A.G. Researcher positionality—A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research—A new researcher guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 8, 4 (Sep. 2020), 1–10; https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1268044

7. England, K.V.L. Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer 46, 1 (1994); https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

8. Wyche, S.P., Hayes, G.R., Harvel, L.D., and Grinter, R.E. 2006. Technology in spiritual formation: An exploratory study of computer mediated religious communications. Proc. of the 2006 20th Anniversary Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. ACM, New York, 2006, 199–208; https://doi.org/10.1145/1180875.1180908

9. Bell, G. No more SMS from Jesus: Ubicomp, religion and techno-spiritual practices. In UbiComp 2006: Ubiquitous Computing (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 141–158; https://doi.org/10.1007/11853565_9

Posted in:

on Tue, August 16, 2022 - 4:29:20

Cori Faklaris

Cori Faklaris is a doctoral candidate in human-computer interaction at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA. She researches the social-psychological factors of cybersecurity and other protective behaviors. She also is a dharma teacher in the Kwan Um School of Zen.

[email protected]

View All Cori Faklaris's Posts

Designing for religiosity: Extracting technology design principles from religious teachings

Authors:

Derek L. Hansen,

Amanda L. Hughes,

Xinru Page

Posted: Thu, August 04, 2022 - 3:16:31

Religious beliefs have a profound influence on billions of people across the globe, affecting nearly every aspect of their lives, including the use of technology. While there is a continuous rise in atheism, the majority of people in many countries still believe in a deity, self-identify with a religion, and regularly participate in religious practices such as prayer. For example, in the U.S., 69 percent self-identify with a religion, 66 percent consider religion very important (41 percent) or somewhat important (25 percent) to their life, and 67 percent pray daily (45 percent) or weekly/monthly (22 percent) [1]. For many people, religious beliefs and teachings frame every aspect of their life, influencing behaviors related to diet, social relationships, dress and grooming, sexual practices, mourning for the dead, raising children, and financial decisions, among others.

It is no surprise, then, that religions have much to say about the use of technologies, such as the Internet, social media, and mobile phones. Yet design guidance is mostly absent on how to design technology in ways that support various religious values and beliefs. While philosophers, sociologists, and humanities scholars have studied the intersection of technology and religion, relatively few studies have examined religion and technology from a design and HCI perspective [2]. This is unfortunate, since religious traditions often seek to transform the lives of their adherents and the world for the better. Such inclinations can be highly compatible with core HCI values, which often focus on the betterment of the world through the novel use of technology.

Few HCI researchers make time to look through the lens of religious teachings at the technologies that surround us [2]. Thus, we don’t fully appreciate basic questions related to religious teachings and technology. How central a role does technology play in religious teachings? What stances do religions take on the appropriate or inappropriate use of technologies? How do religions frame the discussion around technology, given that many of their teachings are based on ancient texts written by those with vastly different technologies? What role does religious doctrine play in informing religious practice around technologies? How do these answers differ for different religious traditions?

Religious values are integral to many people’s lives and should be considered a key value for the HCI community to integrate into technology design. All physical and digital artifacts convey and enforce certain values, whether they are purposefully designed to do so or not. Thus, value clashes can occur when the affordances of the technology are not aligned with the values of the system’s users. In fact, a system that is designed from the perspective of one group may impose the values of that group on other target users of the system. For example, the idea that a mobile phone is attached to one individual and thus a unique phone number can be required for each person’s account setup for an online service may be a fair assumption in many contexts. However, it causes issues for countries, settings, or religious contexts where a mobile phone is a shared object between a married couple, family, or even extended community, creating an account setup roadblock for anyone who does not have their own phone number. Technology infrastructures meant to support people with many different values should account for this diversity of values and validate assumptions about its users.

A very limited number of HCI studies have investigated how technology practices complement or hinder religious practices via empirical studies (we expand on a number of these in the next section). Existing HCI research has also focused on understanding how religious practices can inform design in nonreligious contexts. For example, several studies apply strategies employed by religious organizations to enhance commitment, build community, and/or motivate behavior change in nonreligious organizations. Ames et al. explored how religious ideological practices can serve as a useful lens in understanding how nonreligious engineering and design organizations affirm membership and a shared vision [3]. Similarly, Amy Jo Kim discusses the use of rituals (a concept inspired by religions) in building commitment to online communities [4].

While this prior work gives us initial insights into the interplay of religiosity and technology in practice, there is an element that is missing and yet key to understanding values we might aspire to incorporate into our technologies. While studying how people use technologies in practice gives us a descriptive understanding, there is also a prescriptive element of religion that is vital to understand. In many religions, there are a set of values that believers aspire to, and they hope to engage in practices that reflect those core values. Thus, we need to not only understand how technologies are used in practice, but also the guiding principles that a given population might be influenced by or aspire to. This also helps us to identify new opportunities for supporting religiosity.

How religious doctrine and teachings can inform design

Many religions provide specific prescriptive guidance to their adherents on the use of social media, the Internet, or other modern-day technologies that are of interest to the HCI community. Such guidance is often based upon doctrines, or the foundational beliefs, principles, and teachings of a religion. These come in the form of ancient scriptural texts, commentaries, sermons, pronouncements by religious leaders, official publications of religious organizations (e.g., magazines), and a variety of other resources. While it is tempting to consider only the practical, prescriptive advice about technology use given to members of a religion, it is essential to also understand the religious doctrines and teachings that underly such advice. Designers can benefit in several ways from learning the core doctrinal beliefs of a religion in order to better design for its members.

First, doctrines can inspire the use of religious metaphors that tap into believers’ deepest spiritual desires and insights. For example, Pope Francis used the metaphor from St. Paul’s teachings in the New Testament that views Christians as “members of the one body whose head is Christ” when discussing the importance of using social media to build up others and not tear them down [5]. This metaphor stresses the value of a community (i.e., a body) having different body parts (e.g., eyes, ears, legs, hands), each of which serves a different purpose for the benefit of the whole. By invoking this metaphor, the Pope encourages Catholics to see the Church as “a network woven together by Eucharistic communion [a central Catholic ritual, where unity is based not on ‘likes,’ but on the truth, on the ‘Amen,’ by which each one clings to the Body of Christ, and welcomes others.” Religious metaphors can summon strong emotions and spiritual insights in believers, providing motivation to use technology in certain ways (e.g., being kind in online discourse).

Second, understanding religious doctrine and teachings can help designers solve problems and achieve goals that are religious in nature. For example, Woodruff et al. studied the home automation practices of American Orthodox Jewish families [6]. Jewish laws generally prohibit manually turning electronic devices off or on during the Sabbath. These families had long designed and automated systems within their home that would perform mundane tasks (e.g., turning lights on/off with timers or sensors) to abide by this law. Without a deep understanding of Jewish teachings and practices, designing to meet their needs would not be feasible. Another example comes from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, whose doctrine encourages members to be eternally “sealed” (i.e., connected) to their family, including deceased ancestors through vicarious ordinances performed in their Temples. This focus has led them to invest significant resources in developing genealogical tools that help members identify their ancestors, such as FamilySearch, which has a collaboratively generated family tree with over 1.38 billion names and had over 200 million site visits in 2021. Additional tools allow church members to track and manage the vicarious work that members perform in the Temples. Thus, an understanding of the core doctrines related to Temple work has been essential to the development of unique tools that support such work.

Third, understanding religious teachings can help designers modify existing technologies to better meet the needs of believers. For example, HCI researchers have recognized that technologies supporting financial services within Muslim communities must work within a religious framework where charging interest is forbidden [7]. Thus, micro-lending websites that rely on interest must be modified in fundamental ways to be viable solutions in Muslim communities. Many religions have their own dating sites, helping people find singles with a similar religious background. In some cases, these include specific features that differ from general dating websites. For example, Shaadi is a popular Hindi “matrimonial” website with 35 million users that focuses on finding a spouse rather than hookups.

Finally, understanding religious doctrines can help designers identify core values that can then be used to design solutions that are in harmony with and reflect a believer’s core beliefs. Susan Wyche and Rebecca Grinter [8] examined how American Protestant Christians use ICT in their home for religious purposes. Their findings suggest many opportunities for designing systems that acknowledge, honor, and support religious values in a domestic setting, such as creating digital calendars and displays that recognize and change their content based on significant religious holidays or milestones. In 2005, an Israeli wireless company launched a mobile phone specifically designed for the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Israel [9]. The phones were modified to disable Internet, text messaging, and video and voice messaging, after religious authorities and community members became concerned that these services could infiltrate the community with unacceptable content.

There are many open questions about how to best use religious doctrines and teachings in design. How can design methods be modified to incorporate and prioritize religious teachings? How can products be evaluated based on religious teachings? How can technology help achieve uniquely religious goals, for which technology has not historically been used? How can systems be designed that meet the needs of diverse religious groups, given their different teachings? What values can be derived from religious teachings that can be incorporated into design?

In asking these questions that seek to understand the prescriptive aspect of religious values in the context of technology use, we can better understand which values people may want represented in technologies. We also hope that this work will serve as a call to action for the HCI community to engage more holistically with religious values. A set of values that are such an integral part of so many peoples’ lives should be acknowledged and given priority; HCI should support people’s priorities and values. We call on the HCI community to take steps toward understanding the interplay of religious values and technology to be able to create truly value-sensitive technologies.

Endnotes

1. Smith. G.A. About three-in-ten U.S. adults are now religiously unaffiliated. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. Dec. 14, 2021; https://www.pewforum.org/2021/12/14/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-are-now-religiously-unaffiliated/

2. Buie, E. and Blythe, M. Spirituality: There’s an app for that! (but not a lot of research). CHI’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2013, 2315–2324; https://doi.org/10.1145/2468356.2468754

3.Ames, M.G., Rosner, D.K., and Erickson, I. Worship, faith, and evangelism: Religion as an ideological lens for engineering worlds. Proc. of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. ACM, New York, 2015, 69–81; https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675282

4. Kim, A.J. Community Building on the Web: Secret Strategies for Successful Online Communities. Peachpit Press, 2006.

5. Pope Francis. Message of His Holiness Pope Francis for the 53rd World Communications Day. 2019; https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/messages/communications/documents/papa-francesco_20190124_messaggio-comunicazioni-sociali.html

6. Woodruff, A., Augustin, S., and Foucault, B. Sabbath day home automation: “It’s like mixing technology and religion.” Proc. of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2007, 527–536; https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240710

7. Mustafa, M et al. IslamicHCI: Designing with and within Muslim populations. Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2020, 1–8; https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3375151

8. Wyche, S.P. and Grinter, R.E. Extraordinary computing: Religion as a lens for reconsidering the home. Proc. of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2009, 749–758; https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518817

9. Campbell, H. ‘What hath God wrought?’ Considering how religious communities culture (or Kosher) the cell phone. Continuum 21, 2 (2007), 191–203; https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310701269040

Posted in:

on Thu, August 04, 2022 - 3:16:31

Derek L. Hansen

Derek L. Hansen is a professor at Brigham Young University’s School of Technology’s information technology program. His research focuses on understanding and designing social technologies, tools, and games for the public good. He has received over $2 million in funding to develop and evaluate novel technical interventions, games, and simulations.

[email protected]

View All Derek L. Hansen's Posts

Amanda L. Hughes

Amanda L. Hughes is an associate professor of information technology in Brigham Young University’s School of Technology. Her current work investigates crisis informatics and the use of information and communication technology (ICT) during crises and mass emergencies, with particular attention to how social media affect emergency response organizations.

[email protected]

View All Amanda L. Hughes's Posts

Xinru Page

Xinru Page works in the field of human-computer interaction researching privacy, social media, technology adoption, and values in design. Her research has been funded by the NSF, Facebook, Disney Research, Samsung, and Yahoo! Labs. She has also worked in the information risk industry leading interaction design and as a product manager.

[email protected]

View All Xinru Page's Posts

Faith informatics: Supporting development of systems of meaning-making with technology

Authors:

Michael Hoefer,

Stephen Voida,

Robert Mitchell

Posted: Mon, July 25, 2022 - 3:23:37

In seeking to apply HCI to faith, religion, and spirituality, we turn to existing work in theology and psychology—in particular, work that studies the development of faith in individuals and communities. James Fowler is a pioneer in faith development, having developed a stage-based model after conducting over 300 interviews with individuals from a variety of religions [1]. In his work, Fowler suggests that faith is universal to all humans, and he provides an understanding of faith that we believe would serve the HCI community in grounding further efforts to integrate HCI practice with spirituality, faith, and religion.

Fowler describes how most religious organizations fall short in supporting the development of faith in their constituents, as they fall prey to a modal developmental level—the most commonly occurring level (the mode) of development for adults in a given community (empirically, stage 3 of 6, explained in depth below). In other words, the developmental level that is most common in the adults of a community shapes the culture and normative goals of individuals growing up in that community, which Fowler calls an “effective limit on the ongoing process of growth in faith” [1].

HCI researchers are good at understanding how individuals form and act upon mental models. That is one of our aims when we try to develop technology: to understand people and what might help them. In helping individuals with their systems of meaning-making (faith), we might want to do something very similar. This, we suggest, is one of the prime challenges and opportunities for HCI researchers when engaging with faith and spirituality: to seek to understand and support individuals through their faith-ing. Here, we outline future research directions for what we are calling faith informatics: the study of systems that facilitate growth in individuals’ systems of meaning-making.

One direction for faith informatics could involve structured reflection, visualization of the self, and social connection. One goal might be to reify the existence of all stages of faith, beyond the normative, modal developmental levels present in many faith-based communities. By developing systems that support faith development regardless of religious (or nonreligious) orientation, computing and HCI hold the promise of supporting faith development and maintenance, highlighting convergence across religious traditions and supporting universal mature faith.

Faith as fundamental to the human experience

The word faith is often associated only with “belief,” in that having faith is just a matter of what one believes to be true. Wilfred Cantwell Smith suggests an alternative: that faith is not dependent on belief [2]. In this vein, faith is neither tentative nor provisional, while belief is both.

Fowler draws on this and suggests an alternative conceptualization that views faith and religion as separate, but reciprocal [1]. Fowler views religion as tradition that is “selectively renewed,” as it is “evoking and shaping” the faith of new generations. Faith is an aspect of the individual, while religion represents the tradition of the culture in which the individual grows and develops. Faith is an aspect of every human life, an “orientation of the total person,” and, as a verb, an “active mode of being and committing.” Faith is considered to be “the finding of and being found by meaning” [3]. This focus and widening of faith to include the association with meaning-making is not only inclusive of many religious and spiritual traditions, but is also vital in nonreligious traditions such Alcoholics Anonymous’s 12-Step Program. For HCI, this conceptualization resonates with existing research developments devoted to understanding the role of computing in finding and supporting meaning-making [4].

Specifically, Fowler describes three contents of faith that every human subconsciously holds in mind as they go about their life: 1) centers of value, which are whatever we see as having the greatest meaning in our lives, 2) images of power, which are the processes and institutions that sustain individuals throughout life, and 3) master stories, narratives we believe and live that facilitate our interpretation of the lived experience [1].

If faith is a universal human condition, as suggested by Fowler and Smith, then HCI researchers have much more purchase to engage with research questions related to faith, as that work would therefore have the potential to be applied to all of humanity.

Stages of faith development

Fowler describes a series of six stages of faith that are loosely aligned with age during the beginning of life, but development can be arrested in any stage [1]. Similar to Robert Kegan’s forms of mind [5], each progressive stage of faith is represented by a changing relationship between subject and object as an individual starts to consider a larger system as part of the “self” with regard to meaning-making. An overview of each stage suggests a diversity of use-cases for faith informatics.

Stage 1: Intuitive-projective faith. According to Fowler’s interviews, intuitive-projective faith is found in 7.8 percent of the population and is the dominant form found in children ages three to seven. Intuitive-projective faith is marked by fluid thoughts and fantasy, and is the first stage of self-awareness. Fowler explains that transitioning out of stage one involves the acquisition of concrete operational thinking and an ability to distinguish fantasy from reality.

Stage 2: Mythic-literal faith. Mythic-literal faith is estimated to be found in 11.7 percent of the population, and largely in children ages seven to 12. Mythic-literal faith involves the individual starting to internalize the “stories, beliefs, observances that symbolize belonging to his or her community.” Individuals in this stage create literal representations of centers of power, which often involves anthropomorphizing cosmic actors. Individuals in this stage may take religious texts literally as a foundation for meaning-making. While Fowler’s work did find a handful of adults in stage 2, many would transition out of this stage in their teenage years, as they experienced multiple stories that clashed and required reflection to integrate.

Stage 3: Synthetic-conventional faith. Synthetic-conventional faith is the most commonly found stage of faith in Fowler’s sample, and appears in 40.4 percent of the population. Transitioning into this stage often occurs around puberty, and is associated with a growing connection to social groups other than the family, perhaps with different collective narratives and centers of value. Synthetic-conventional faith systems attempt to “provide a coherent orientation in the midst of that more complex and diverse range of involvements...synthesize values and information...[and] provide a basis for identity and outlook.”

This stage is highly aligned with Kegan’s view of the self-socialized mind [5]; both are intended to deal with meaning-making involving multiple social relations and belonging to various social groups. In this stage, individuals create their personal myth: “the myth of one's own becoming in identity and faith, incorporating one's past and anticipated future in an image of the ultimate environment.” Transitioning to the next stage often involves a breakdown in the coherence of the meaning-making system, such as a clash with religious or social authority or moving to a new environment (i.e., leaving home).

Stage 4: Individuative-reflective faith. Developing an individuative-reflective faith system (32.9 percent of the population) requires an “interruption of reliance on external sources of authority.” Individuals in this stage are characterized by separation from previously assumed value systems, and the “emergence of an executive ego.” Fowler notes that some individuals may separate from previous value systems, but still rely on some form of authority for meaning-making, which can arrest faith development in the transition to individuative-reflective faith. This stage involves taking responsibility for one’s “own commitments, lifestyle, beliefs, and attitudes” and would be aligned with Kegan’s “self-authoring” form of mind.

Stage 5: Conjunctive faith. Stage five, according to Fowler, is difficult to describe simply. Conjunctive faith was found in only 7 percent of the population, and not until mid-life (ages 30 to 40). Conjunctive faith involves a deeper acceptance of the self, and integrating “suppressed or unrecognized” aspects into the self, a kind of “reclaiming and reworking of one’s past.” This stage is similar to Kegan’s self-transforming mind, as both involve the embrace of paradox and advanced meta-cognition about the self. Individuals in this stage must live divided between “an untransformed world” and a “transforming vision and loyalties,” and this disconnect can lead individuals into developing rare universalizing faith systems of meaning-making.

Stage 6: Universalizing faith. Stage six represents a normative “image of mature faith” that was found to be present in only one interview participant [1]. Fowler describes these individuals as:

grounded in a oneness with the power of being or God. Their visions and commitments seem to free them for a passionate yet detached spending of the self in love. Such persons are devoted to overcoming division, oppression, and violence, and live in effective anticipatory response to an inbreaking commonwealth of love and justice, the reality of an inbreaking kingdom of God [3].

Developing a universalizing faith is seen as the “completion of a process of decentering from the self” [3], described by:

taking the perspectives of others...to the point where persons best described the Universalizing stage have completed that process of decentering from self. You could say that they have identified with or they have come to participate in the perspective of God. They begin to see and value through God rather than from the self...their community is universal in extent [3,4].

The goal of faith informatics, as a direction of inquiry, is to better understand the systems (social, ecological, information, or otherwise) that support faith development and how they can be improved. A tool for research, and perhaps an intervention in itself, may be an information system that allows an individual to gather faith-related data about themselves and then visualize and interact with these representations of the self.

A design paradigm for faith informatics

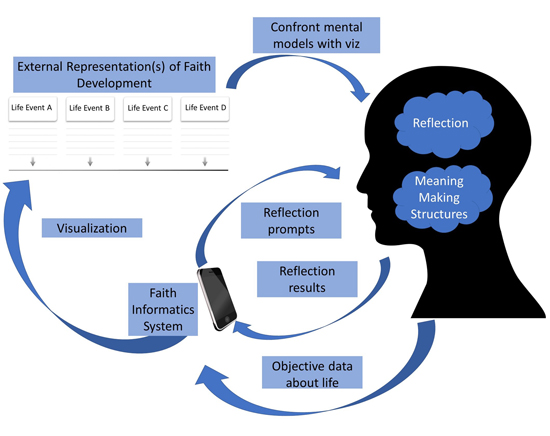

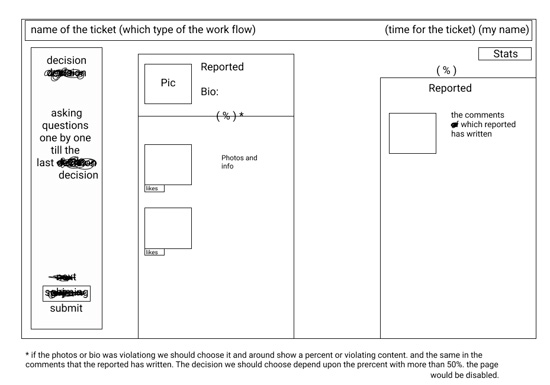

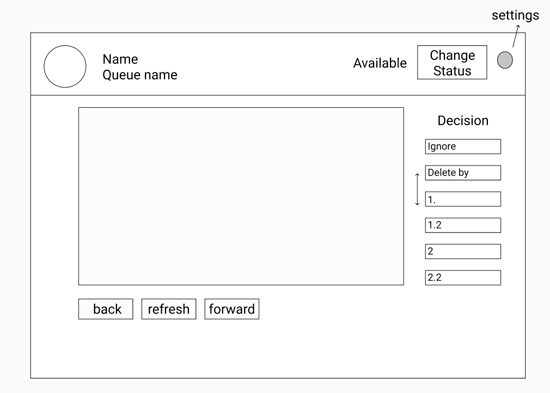

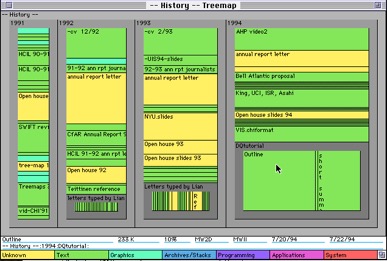

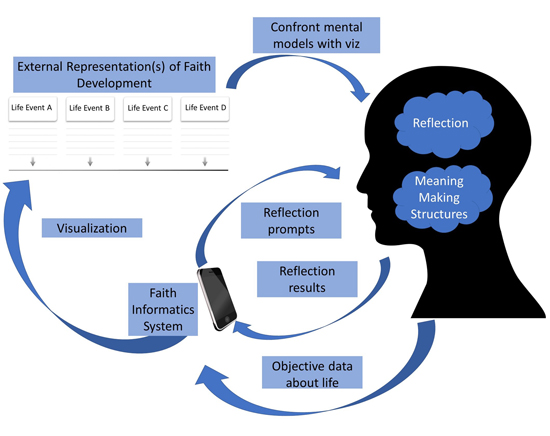

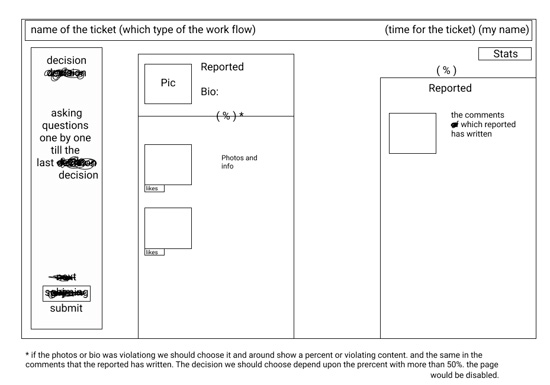

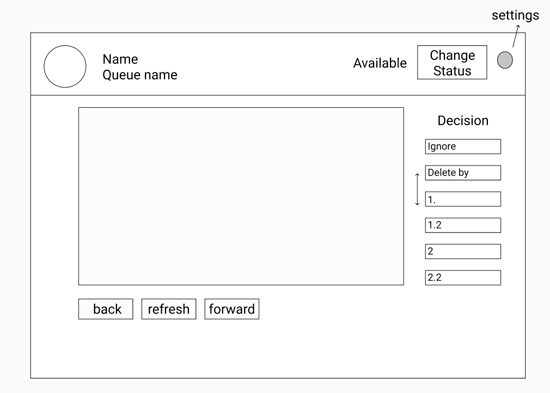

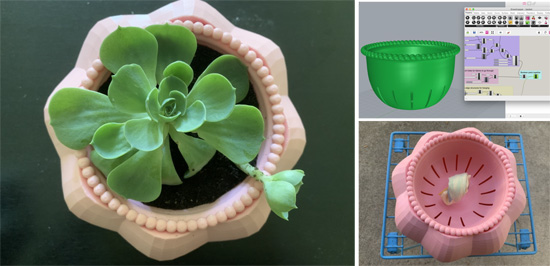

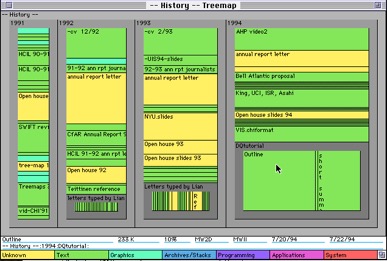

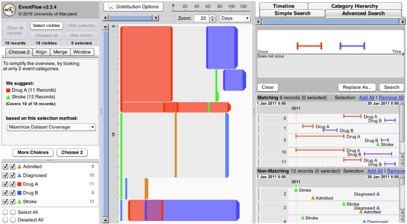

Figure 1 highlights the components of a potential faith informatics system based on a smartphone or other computing-based application (the “system”). The theory behind this system design is drawn from research interviews used by both Fowler in Stages of Faith and Kegan in the subject object interview [5]. Both researchers relied on what we call the “research interview” to determine the stages of faith (or, in Kegan's case, “forms of mind”) present in the individual.

Figure 1. A depiction of a framework for designing faith informatics (FI) systems to support the elicitation and reflective revision of mental models of one's faith. The FI system prompts the user to systematically reflect on themself in the style of Fowler's faith development interviews [1]. This elicitation is combined with objective data about the individual's life and presented to the individual in a visualization. This visualization is then used to reciprocally influence the mental model the individual holds of their faith, facilitating development into further stages of faith.

The interview methodology relies on trained interviewers to communicate with and assess subjects using semi-structured interviews. Questions that might be asked in the interview include (selected from [1]):

- Thinking about yourself at present. What gives your life meaning? What makes life worth living for you?

- At present, what relationships seem most important for your life?

- Have you experienced losses, crises or suffering that have changed or ``colored'' your life in special ways?

- What experiences have affirmed or disturbed your sense of meaning?

- In what way do your beliefs and values find expression in your life?

- When life seems most discouraging and hopeless, what holds you up or renews your hope?

- What is your image (or idea) of mature faith?

One critical insight is that this methodology, by asking these deep questions, appears to support development by itself. Jennfier Garvey Berger notes that individuals who undergo the subject-object interview “changed the way they were thinking about things in their lives” and wanted to “come back for another interview” [6]. Some individuals reported making significant life changes after the interview, such as leaving an unhealthy relationship [6]. Fowler, using his faith development interview, also notes that interviewees tend to say things along the lines of “I never get to talk about these kind of things” [1].

HCI researchers and practitioners can help make these “developmental interview” experiences more available to the general public. The subject object interview is noticeably costly, both in time required for the conducting of the interview (60 to 75 minutes per subject), as well as required training for the researcher. One potential avenue for faith informatics, therefore, is to attempt to recreate the essential conditions of developmental interviews, allowing for the deep reflection that occurs during the interviews.

For example, mobile or Web apps could attempt to recreate the conditions of a conversation that promote self-reflection and capture the outcomes of the reflection. This approach would be aligned with the notion of reflective informatics, which seeks to support reflective practices through technology [7]. Research has already highlighted the promising effects of this kind of digital intervention. The “self-authoring” application, aligned with Kegan's forms of mind (particularly the self-authoring form) has been shown to improve academic performance, reduce gender and ethnic minority gaps, and improve general student outcomes through “future authoring.”

In Figure 1, the hypothetical faith informatics system provides prompts to individuals about aspects of their life related to meaning-making. These prompts may draw from both Kegan’s and Fowler's developmental interviews. In this particular diagram, we use the example from Fowler of eliciting the “life review,” which seeks to break the life history into episodes of meaning [1], and allows for reflection on each stage in life. This is, in essence, a large-scale version of the day reconstruction method—a kind of life reconstruction method—where individuals can break their life up into discrete episodes that mark turning points in their development of meaning-making systems. We envision a role for interactive systems in providing an interface for eliciting the construction of these episodes and any associated metadata (e.g., real-world context).

This is one of the key benefits afforded by an informatics system: the possibility of incorporating real-world, objective data in these reflective dialogues. As an individual’s system of meaning-making would be used for both answering prompts and governing an individual's behavior, the system can play a role in helping an individual compare their own perception of their meaning-making structures with how they (objectively) live their life. For example, life episodes could be colored by social contacts elicited from text messaging or email data, or behavioral activity derived from calendar entries or financial activities.

Faith informatics would therefore also connect with the field of personal visual analytics, where an individual’s data (coming directly from the experiences described earlier) is visualized into an external representation that can enable the individual to confront their mental models of themself and of their life, potentially resulting in reciprocal feedback loops to prompt insights about and support faith development. The design and creation of these visualizations is an open challenge and may benefit from co-design activities and think-aloud visualization interaction studies.

We might expect that an individual’s current stage of faith would inform design decisions. For example, an individual transitioning into stage 5 (conjunctive faith) may benefit from exploring objective data about their life history as they “reclaim and rework” [1] their past.

Facilitating social connections via faith informatics

Another promising avenue for faith informatics is that of fostering social connections that span both religious and non-religious faith traditions. While Fowler's stages of faith are largely based on Western religious traditions, it is possible (and perhaps likely) that similar developmental structures of meaning-making exist across religions and traditional beliefs worldwide, given the focus on structure of faith instead of contents of faith [1]. As such, faith informatics could facilitate the connection of individuals based on stage of development, rather than relying on religious communities that may suffer from the limits of particular modal developmental levels. Such a system could help to connect individuals in similar stages of faith across different cultures, facilitating connection and development, perhaps via the sharing of narratives and experiences.

Challenges and future work in faith informatics

Faith informatics is ripe with challenges and opportunities for the HCI community. One significant challenge is in the visualization of representations of faith that facilitate systematic reflection about an individual’s meaning-making structures. While we can draw upon Fowler’s research interview methodology to understand the types of prompts that may facilitate individual faith development, this kind of data (to our knowledge) has not previously been explored with contemporary visualization techniques. We expect that advances in personal visual analytics are necessary to support the effective visualization of self-reported faith data in a way that promotes development.

In addition, the HCI community must confront the undigitizable nature of faith and spirituality, especially with regard to users in the later stages of faith. Fowler only encountered one individual in stage 6, the universalizing faith stage. It may be difficult to attempt to reify late stages of faith in a digital system, especially when the presence of these stages is limited to few individuals. Future work could include in-depth interviews with individuals in these advanced stages of faith to better understand their life trajectory, in hopes of better understanding and sharing how they reached these particular forms of meaning-making.

Endnotes

1. Fowler, J.W. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. HarperCollins, New York, NY, 1981.

2. Smith, W.C. Faith and Belief: The Difference Between Them. OneWorld Publications, Oxford, U.K. 1998.

3. Fowler, J.W. Weaving the New Creation: Stages of Faith and the Public Church. Wipf and Stock Publishers, Eugene, OR, 2001.

4. Mekler, E.D. and Hornbæk, K. A framework for the experience of meaning in human-computer interaction. Proc. of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, NY, 2019, Article 225; https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300455

5. Kegan, R. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA, 1998.

6. Berger, J.G. Using the subject-object interview to promote and assess self-authorship. Development and Assessment of Self-Authorship: Exploring the Concept Across Cultures. M.B. Baxter Magolda, E.G. Creamer, and P.S. Meszaros, eds. Stylus Publishing, Sterling, VA, 2010, 245–263.

7. Baumer, E.P.S. Reflective informatics: Conceptual dimensions for designing technologies of reflection. Proc. of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, NY, 2015, 585–594; https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702234

Posted in:

on Mon, July 25, 2022 - 3:23:37

Michael Hoefer

Michael Hoefer is a third-year Ph.D. student studying computer and cognitive science at the University of Colorado Boulder. He is generally interested in studying social systems at various scales, and developing informatics systems that serve as problem solving interventions at each level. His application areas include dreaming, sustainability, and systematic well-being.

[email protected]

View All Michael Hoefer's Posts

Stephen Voida

Stephen Voida is an assistant professor and founding faculty of the Department of Information Science at CU Boulder. He directs the Too Much Information (TMI) research group, where he and his students study personal information management, personal and group informatics systems, health informatics technologies, and ubiquitous computing.

[email protected]

View All Stephen Voida's Posts

Robert Mitchell

Robert D. Mitchell is a retired pastor in the Desert Southwest Conference of the United Methodist Church and an Oblate in Saint Brigid of Kildare Monastery. He holds a Ph.D. in education and formation from the Claremont School of Theology.

[email protected]

View All Robert Mitchell's Posts

Stream switching: What UX, Zoom, VR, and conflicting truths have in common

Authors:

Stephen Gilbert

Posted: Wed, July 20, 2022 - 12:08:28

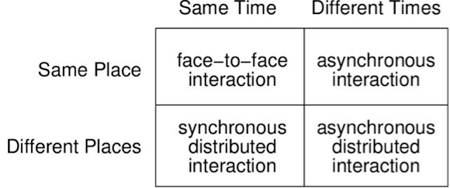

I use the term stream switching to refer to people simultaneously processing multiple streams of input information, each of which has its own context and background knowledge. This definition sounds similar to multitasking, but multitasking research usually focuses on a single individual, divided attention, and working memory capacity. Stream switching focuses on multiple people’s interactions and their mental models of each other. Below I offer examples and argue that stream switching merits further research.

Stream switching

Stream switching draws on 1) the economic concept of switching costs and 2) the psychological concepts of perspective-taking and theory of mind. Economic switching costs are the financial, mental, and time-based costs to switch between products. The costs of switching from an Android to an Apple phone, for example, go far beyond the price tag and include learning how to use the phone’s software and much personal information transfer. Analogously, stream switching includes not only the basic attentional cost of focusing on a different input stream, but also the additional cognitive load of updating one’s mental model of the stream source. Is it accurate? Is it trustworthy? These questions relate to the psychological concepts of perspective-taking (Can you imagine others’ perspectives?) and theory of mind (Can you understand how different others’ knowledge and beliefs might be from yours?).

Stream switching includes the more specific practice of code-switching. Code-switching was originally the linguistic practice of switching between languages depending on your context, and now refers more generally to the switching of identities depending on who’s around you. Someone might behave one way at home with family and another way in the outside world. Minorities often become quite skilled at code-switching since they have daily practice working within a different majority culture. I would hypothesize they are also highly skilled at stream switching.

The idea that people vary in their stream switching ability is one of the reasons stream switching deserves more research. Can this critical skill be practiced or trained? We already know that some people are better than others at empathizing, understanding what other people are thinking and feeling. Research has correlated these individual differences with factors including reading more fiction, role-playing and reflection, the general practice of thinking more about one’s thinking. Perhaps this research could be extended to develop methods to measure one’s stream switching ability and methods of improving it.

User experience (UX) implications

In user-centered design, we try to empathize with our users. We create personas to reduce our cognitive load of doing so. Here is Maria, the young professional with two children; what are her jobs to be done when she opens our app? A product designer with better stream-switching skills will truly be able to step into Maria’s world and build an accurate mental model of her goals and expectations in order to design a product that fits perfectly. That product then allows Maria to accomplish her goals more quickly with fewer errors.

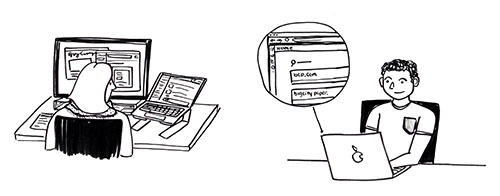

On the other hand, low-usability software requires the user to switch streams mid-use to imagine the intentions of the software designer or to model the inner workings of the software itself. You may have experienced an accounting system that was well-designed for accountants but not for you. While the accountants can easily track expenses, you can’t figure out how much money you have. Or consider a social media system. If you post certain content, is it clear who will see it? Will it lead your friends to see related ads? Or in a corporate calendaring system, if you invite people to a meeting, is it clear who will see the invite list? Being able to answer these questions requires highly usable software. Norman warned about gulfs in evaluation; today’s sociotechnical context requires evaluation of not only the system, but also of other users’ experiences with it.

Frustrating usability situations increase stream switching, which burdens our cognitive capacity. When you have to switch streams to figure out where to click next, you have less attention to devote to the streams you were already juggling, for example, home life versus work life, or your supervisor’s mindset versus your teammates’. Bad interaction designs effectively steal our attention.

Asymmetry, monitoring, and conflicting versions of truth

Many systems present asymmetric information to users, i.e., collaborators receive different information or levels of access, as in the calendaring example. It’s not always a problem; a person presenting slides should be able to see their presenter notes while the audience should not. But when you’re Zooming and ask, “Can you hear me?” or “Can everyone see my screen?”— that’s problematic asymmetry. You don’t have good cues about what other people are experiencing, so you have to ask explicitly. Having this information enables you to update your mental model of your colleagues’ experience in the meeting and enables you to stream switch more smoothly between conveying your points and monitoring your colleagues’ understanding.

Asymmetric stream switching also appears if you use a virtual reality headset. When you enter the virtual world, you partially blind yourself to cues in the real world. To avoid tripping over a nearby chair, you need to switch streams consistently to monitor both the virtual world and the real world. If you carefully arrange the furniture in your room beforehand, creating a safe space for virtual exploration, then you can reduce the mental workload required to monitor that stream and focus more on the virtual stream with less overhead.

Analogously, as supported by research on stereotype threat and Goffman’s idea of roles that people play in life, when people have a metaphorical “safe space” for collaboration with others despite diverse backgrounds, they can focus less on monitoring the stream of how they’re being perceived (“Will I say something offensive?”) and more on the stream of the collaborative task at hand.

Finally, consider the number of people who have difficulty speaking with each other because of their dramatically different beliefs about what is true. This is a stream-switching problem with high asymmetries. It has become more difficult than ever before to imagine what it’s like to be on the other side, because the affordances to do so barely exist. Only by investing significant time in creating alternative social media accounts and filling them with clicks could someone start to experience the other’s perspective. The cognitive load of stepping into the shoes of the other person has become so high that it’s easier to discount them as foolish or deceived. It’s easier to stream switch and model the perspective of someone similar to yourself. In part, that’s why similar people are drawn to one another. But there is a very high likelihood that many people we work with, as well as our customers, are not similar to us. Research on the “contact hypothesis” shows that talking with people who are different than ourselves enables us to understand their perspectives with more empathy, even if it’s difficult. More than ever before, we need to increase our stream-switching abilities, which will enable us to understand others.

Thanks to Joanne Marshall and Kaitlyn Ouverson for thoughtful feedback on these ideas.

Posted in:

on Wed, July 20, 2022 - 12:08:28

Stephen Gilbert

Stephen B. Gilbert is associate director of Iowa State University's Virtual Reality Application Center and director of its human-computer interaction graduate program, as well as an associate professor in industrial and manufacturing systems engineering. His research interests focus on technology to advance cognition, human-autonomy teaming, and XR usability.

[email protected]

View All Stephen Gilbert's Posts

Unavailability: Food for thought from Protestant theology

Authors:

Sara Wolf,

Simon Luthe,

Ilona Nord,

Jörn Hurtienne

Posted: Tue, July 19, 2022 - 9:45:16

The past two years of living in pandemic times have accelerated the spread of technology into all areas of life. This was also evident in the context of religious communities and churches, where the number of applications and users has increased enormously. Not only individual communities but also the great church institutions had to expand their presence in the digital sphere [1]. As a result, interaction with technology in religious and spiritual contexts is now more widespread than even a few years ago. Understanding how technology and interaction design influence experiences in such contexts is more important than ever. However, this increased need for knowledge is not yet visible in HCI publications. We also believe that through more research in these areas, HCI can gain new perspectives on technology use, design, and evaluation more generally. Similar to how work on religious objects in households inspired a broader call for extraordinary computing [2] , we would like to introduce a theme that emerged from our work with Protestant believers, and that can bring new impetus to HCI: unavailability.

We derive this claim from a continued cooperation between HCI researchers and Protestant theologians. Together, we have been working on several projects that aim at designing technology for religious communication in the form of rituals, blessings, and online worship services. In the following, we want to demonstrate that integrating aspects of faith, religion, and spirituality in HCI might be valuable and lend HCI new perspectives.

Unavailability

The development of current technology is about making everything available at any time: Vast amounts of music and films are available through media streaming services, our loved ones are available through video (chat), and worship services are available online. In most of the Western world, many of our desires can be fulfilled immediately using technology, which focuses on making everything visible, accessible, controllable, and usable [3]. However, this ubiquitous availability might not always be valuable. Sometimes the opposite, unavailability, might be the better choice. Unavailability can highlight what one values most about what is available and can evoke the experience of resonance, specialness, or meaning. In the following, we will present two examples that demonstrate how we came across the theme of unavailability in our research.

The first example originates in our work on blessings. In a design probe study with Protestant believers, we tried to understand what blessing experiences are, and where or when they happen in believers’ everyday lives. Participants described that the feeling of being blessed can occur anytime, anywhere, but is most intense when it is unexpected and surprising (i.e., unavailable). One participant shared the following story when asked to describe an experience of being blessed:

I had a conversation with a friend who told me about her happiness as a mother, how it was to hold her newborn baby in her arms for the first time, how much love she was surrounded by, and how proud she was. And that was very strange for me because she had to deliver the child dead. And, um, I didn’t expect that. And at that moment, well, that was so.... so that overwhelmed me…. So she knew her child would be born dead, she knew she would have a silent birth, and yet there was a lot of pride and happiness and love, and she is still proud to be a mother, even though her child was born dead. And I just find that..."Wow"! So my rational brain said, "Well, that cannot be for real, that doesn’t fit," and I was also afraid of the conversation with her. Um, and then I was, so that’s what got me… So that was surprising, yes, or maybe also what I hoped for. So sometimes it [the blessing] is also a fulfilled hope.

Not all examples of blessing experiences were as drastic as the one described here. However, this story demonstrates the aspects of unexpectedness and surprise very well. The participant did not expect that the conversation with her friend could take place in a positive atmosphere—she was even afraid of the conversation. And then everything turned out quite differently than expected. She could not have worked out this twist or influenced the situation in this direction with certainty—it simply came as it came. The unavailability was also evident in other examples within the same study. Many participants described that they used to bless each other, although they can never be sure whether the blessings are effective—it is beyond their control. For our participants, Protestant believers, this control was attributed to God. The aspect of unavailability generated friction and excitement in people’s experiences: It opened up room for hope, speculation, and surprise—for example, when something absolutely unexpected and positive happens.

Our second example on unavailability shows the opposite: namely, what happens when the unavailable becomes available? In another project, we investigated the experiences of online worship services during the pandemic [4]. We accompanied Protestant believers while participating in online worship services and tried to understand how specific design elements lead to specific experiences. One prominent element that influenced the experiences dramatically was availability and ease of access. Usual worship services are not an everyday occurrence for believers, but rather something special; believers usually invest some effort to mark the worship service as distinct from everyday life and routines—for example, dressing up, going to a special place, and reserving the time to attend. In contrast, online worship services are available anytime and anywhere, which invites specific modes of usage (e.g., watching it on the side).

One couple reported a situation that shows the tensions such constant availability can create. On one Sunday, the couple woke up later than usual, and were in the middle of their breakfast when realizing that the worship service was about to start. Invited by the flexible and accessible design of current online worship services, they watched it using a laptop at their breakfast table. Although this was practical, they quickly became annoyed with themselves. They realized that they had turned what formerly had been an extraordinary experience into something ordinary. Availability changed the way worship services were experienced. The online worship service turned into something everyday and less essential. Constant availability may be convenient and allow for flexible access. However, convenience and flexibility are nothing compared with the cherished unavailability of worship services that take place only at a specified place and time and are unavailable in between.

So far, unavailability seems to be a concept that is given little consideration in HCI, and that even opposes current trends of making everything available. The two examples show how unavailability affects experiences. We think it is worth looking at the concept more closely, as it can reveal new perspectives on technology design. In the following, we will turn to sociology and Protestant theology in order to learn more about the concept of unavailability. Theology has long been concerned with unavailability, and sociology shows how the concept of unavailability is essential for human experiences beyond the context of religion, faith, and spirituality.

The German sociologist Hartmut Rosa has studied unavailability (German: Unverfügbarkeit; he translates it as “uncontrollability”) in his works [3,5]. Rosa describes our time as a time of acceleration, suggesting the concept of resonance as a possible solution [5]. For Rosa, resonance is a type of world relationship formed by affection and emotion, intrinsic interest, and the expectation of self-efficacy, in which subject and world connect and at the same time transform each other. That is, the nature of the world relationship is to be understood as reciprocal. Not only is the relationship defined between subjects and objects, but they also define a new relationship to the world [5]. The experience of resonance is opposite to the experience of alienation, a world relationship in which the subject and the world are indifferent or hostile (repulsive) to each other and thus inwardly disconnected from each other—a relationship of "relationshiplessness" [5]. For Rosa, resonance is the human motivation that guides all actions. A central, constitutive aspect to resonant experiences is unavailability. Four conditions for resonant experiences must coincide [3]:

- Touch (something touches me)

- A response to the touch

- Transformation: a change of world-relationship

- Unavailability.

Even if conditions one to three are fulfilled, unavailability is necessary for a successful, resonating experience. The individual experience of the world can be neither planned nor accumulated. This perspective highlights a fundamental problem with the current focus on making everything available through ubiquitous technology: It is not the availability that renders experiences successful, resonating, and thereby valued but rather their specific quality. And part of what makes their quality is that people are not in control of everything and cannot make the world available to the last. It is precisely in this that Rosa sees a necessity. Space must be given to the concept of unavailability because only in this way are resonating experiences possible [3].

Regarding Christian religion, the necessity of the unavailable for a successful world experience as described by Rosa becomes particularly clear. All objects of the Christian religion, such as God, Christ, the Holy Spirit, grace, living a fulfilled life, and blessings, cannot be made controllable to human beings; they cannot be commanded. Even in an increasingly secularized world, the objects of religion and their unavailability remain something that fascinates and attracts people—albeit no longer only in the forms of the established religious communities. This search for meaning is both an attempt to make the unavailable available and the realization that ultimately unavailability is constitutive for religious experiences. It is precisely this unavailability that makes dealing with the objects of religion interesting to people. If God, the Holy Spirit, or Christ were made available, religion would become uninteresting and lose relevance for the resonant experiences as illustrated above.

The theme of unavailability prompts HCI to reconsider current trends of making everything available. Recognizing that unavailability might be an essential experiential quality, HCI is challenged to engage in the topic. How can unavailability be experienced when interacting with technologies? What ways, if any, are there to design for the unavailable?

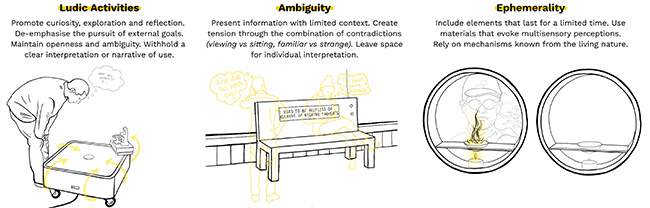

To design or not to design?