Authors: Steve Benford

Posted: Tue, July 23, 2013 - 11:00:32

I’m Steve Benford, professor of collaborative computing at the University of Nottingham’s Mixed Reality Laboratory. My research explores new interaction techniques and concepts for creative and cultural experiences. I characterise my approach as performance-led research in the wild, meaning that my team initially helps artists and performers develop and tour new experiences, which we then study in the wild, ultimately leading to new HCI concepts, such as ambiguity, spectator interfaces, uncomfortable interactions, and trajectories. I was elected to the CHI Academy in 2012 and have won CHI best paper awards in 2005, 2009, 2011, and 2012. My book Performing Mixed Reality has been published by MIT Press. You can find out more about my research, including accessing papers and videos, at my personal research blog.

Trajectories into practice

Maybe it’s an age thing, but I’m increasingly bothered by the question of how my research might make a difference—why might a professional working at the coalface of user experience design be bothered about what I am doing? Of course, there are probably other reasons why this is bothering me too—we (researchers) are increasingly asked to justify the impact of our research, both speculatively when writing proposals such as the “pathways to impact” section on EPSRC proposals, or when our results are weighed in the balance of various assessment exercises such the fast-approaching UK’s Research Excellence Framework, which for the first time includes impact case studies.

An important aspect of this for me is putting HCI theory into practice, a notoriously difficult challenge as articulated by Yvonne Rogers in her recent book on HCI Theory, but also emphasised by EPSRC’s recent review of the state of HCI here in the UK. Perhaps the first question to consider is what I mean by HCI theory here? In addition to Yvonne’s book, which tackles this question in considerable depth, I’ve also been struck by Kia Hook’s and Jonas Lowgren’s recent TOCHI paper on “Strong Concepts,” design abstractions that generalise across different domains. Kia and Jonas identify my work on trajectories as an example of a strong concept, a form of HCI theory that could be ripe for putting into practice.

The question of how to put trajectories into practice has therefore emerged as a central concern for my ongoing EPSRC Dream Fellowship. So far, I’ve been focusing on two different domains, museums and television.

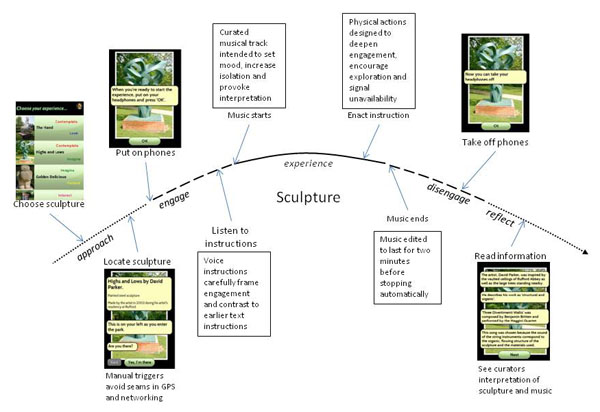

For museums, Horizon Doctoral Training Centre student Lesley Fosh has designed and studied an example trajectory through a sculpture garden (see Figure 1) that aims to move pairs of visitors between moments of experiential engagement with sculptures in which they are isolated, listening to music and performing physical gestures such as touching them, and other moments where these visitors come together again to reflect on these experiences as well as on more “official” guide information that they receive afterwards. These ideas are now being carried forward in the European CHESS project, where we are working with the Acropolis Museum in Athens and the Cite De L’Espace space museum in Tolouse among other partners, including running a series of design workshops over this summer to apply trajectories to the design of new visiting experiences.

Figure 1. Design of the local trajectory through a piece of sculpture in a sculpture garden.

Turning to television, I recently spent four months as a visiting professor at the BBC focusing on the design of multiscreen TV experiences. I began by analyzing some existing companion apps for TV shows, including the Antiques Roadshow play-along game in which viewers estimate the value of antiques during the show, as well as a research prototype called Jigsaw developed by Maxine Glancy and the team at BBC R&D that aims to support intergenerational TV experiences by enabling children to snap images from a TV show and turn them into jigsaw puzzles. Similar to Lesley’s example, I was able to produce some case studies to illustrate the potential of trajectories, albeit by analyzing existing designs. Again, these were followed by a design workshop with participants from editorial, user experience, and research and development, at which we used trajectories to explore new design concepts for extended TV experiences, and two subsequent presentations to the wider BBC user experience design team as part of their Northstar One Service design project.

While it was exciting to be able to engage with professional user experience designers who expressed enthusiasm for trajectories, it proved difficult to establish a deep connection between the concepts and specific example designs in short workshops. We therefore hosted the first “trajectorize” course at Nottingham last week. Three different teams—David Ullman and Dan Ramsden from the BBC; Andres Lucero from Nokia and Joel Fischer from the Mixed Reality Lab; and the artists Ben Gwalchmai and James Wheale—brought along three design concepts that we then inspected though the lens of various trajectory concepts over two days. As well as being thoroughly enjoyable, this was the first time that I began to glimpse how trajectories might actually be put into practice, with zesigners being able to produce complex trajectory sketches as a way of challenging and refining their ideas in areas such as designing social encounters, key transitions, and take-home experiences. You can get more of a sense of what happened from the official course structure and materials, but also from Dan’s blogpost after the event.

The initial success of this course suggests to me that there is indeed the potential to embed strong concepts such as trajectories into the practice of professional user experience design, but also that this takes considerable work from both sides—in this case at least a two-day commitment of time to be able to make significant progress. However, I suspect that there is far more to it than this.

First, we need to understand where these concepts sit in the UX design process (our teams were using trajectories to refine existing concepts rather than for ideation).

Second, it feels important to generate some initial case studies based on familiar examples (as we did in both sectors) to generate initial interest in the concepts.

Third, as our course participants observed, it feels like the concepts need an appropriate level of generality, being structured enough that you can repeatedly attack a design from different perspectives, and yet not so prescriptive that they close down creative thinking.

Finally, is the importance of sketching. We have repeatedly shown trajectories as diagrams and encouraged workshop participants to create their own. Creating and labeling trajectory diagrams feels like an important element of the approach, but also brings its own challenges, not least you need a very large sheet of paper to be able to move between overview and the fine detail of annotations. As a result we have begun to experiment with zoomable drawing tools, initially developing a series of trajectory sketches using Prezi, but more recently with my Colleagues Chris Greenhalgh and Tony Glover beginning to develop and now use our own zooming trajectory sketch tool that adds greater structure, sequencing, and also metadata to an evolving sketch.

Putting trajectories into practice is very much a work in progress, and one that I hope to continue over the coming years. My current sense is that it should be possible to put strong concepts such as trajectories to work, but only if we can find the right approach and supporting tools.

Posted in: on Tue, July 23, 2013 - 11:00:32

Steve Benford

View All Steve Benford's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found