Authors: Caroline Sinders, Sana Ahmad

Posted: Thu, June 24, 2021 - 10:02:38

Content moderation is widely known to be hidden from the public view, often leaving the discourse bereft of operational knowledge about social media platforms. Media and scholarly articles have shed light on the asymmetrical processes of creating content policies for social media and their resulting impact on the rights of marginalized communities. Some of this work, including documentaries, investigative journalism, academic research, and the accounts of individual whistleblowers, has also uncovered the practices of moderating user-generated content on social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok. In doing so, the complex and hidden outsourcing relationships between social media companies and third-party companies—often located in different geographical areas—have been made visible. Most importantly, the identification of these companies and their outsourcing practices has brought to public attention the secretive work processes and working conditions of content moderators.

In this article we illustrate the unique method we undertook to examine the software used in the content moderation process. In December 2020, we held two focus-group research workshops with 10 content moderators. Our participants included former and current employees of a third-party IT services company in Berlin that supplies content moderation services to a social media monopoly based in the U.S. Many participants in our study were immigrants, most of whom had lived in Germany for less than five years. For this group, a lack of German-language skills meant fewer employment opportunities, which led them to apply for content moderation jobs. (As this article focuses on the methodological part of our research workshops, we will not elaborate on the recruitment and work process of the participants.)

The content moderation process is highly confidential; employees are forbidden from describing the work they do and how they do it. When crafting these workshops, we were inspired by collective memory practices. The workshops allowed us to use design thinking exercises to uncover and gauge the infrastructural design, user interface, and user experience design of the systems the participants worked with. While design thinking has a broad meaning and definition, it can be used to problem solve and to create new software or designs; we reverse engineered the process and used exercises designed to help frame questions and translate ideas into tangible interfaces and architectural layouts. From her time as a UX designer in industry, Caroline observed that product designers often lean toward building a specific or concrete “thing,” be it a new product, product augmentation, or process when using design thinking exercises. Our goal was to ground the participants in the space of making. By asking people about their day, the hardships they face, the structure of their workday, and how they iteratively approach their work, a foundation is created to think through building something that would support that work. These exercises helped ground the moderators in the logic of how their software functions and spark memories of the software they use. By working with multiple content moderators in a workshop setting, we created a space of organic reflection and comparison of the tools and protocols they used, leading to discussions on how the Berlin-based employer and the social media client managed the work. In holding our workshops, we followed necessary research protocols, informed by the research ethics standards of the WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

The workshop was divided into five exercises, with each exercise iterating off the previous one. It began with participants writing out a workflow of their day, such as the first thing they see when they log in, what do they do after logging in, where their tasks are stored, and how they engage in tasks. Activities belonging to the first, second, and third exercises were aimed at deciphering the layouts, workflows, and design. Activities four and five had a group discussion format that invited participants to share their experiences of workplace surveillance and propose work-related changes and potential improvements.

Designing the Workshops

Ensuring the privacy of content moderators was integral to this project. Considering the company’s secretive work practices, we were aware of the potential threats to moderators’ job security; therefore, they were not requested to provide screenshots of their work. As an additional precautionary measure, the wireframes have been redrawn for this article. The workshops were held using the audio communication function of a Web-based, open-source software, with appropriate attention given to anonymizing the participants.

Apart from privacy considerations, there were other challenges. To examine the infrastructural design, UX, and UI of the software, we needed to guide participants through the process to draw the software they used for moderating content. Design is a specific medium with a language and vernacular of its own. Content moderators may not know the names of or how to describe the elements in the software they use. Therefore, we designed the flow of activities to accommodate this constraint and guide the moderators through an ideation process that could ensure their participation. Our approach was to create exercises that slowly, organically, and iteratively helped the participants sketch the software they used.

Workshop Structure

Both workshops began with presentations by the organizers. Sana introduced the existing studies on the labor process of content moderation and the importance of undertaking this research project, followed by Caroline, who explained basic design elements that we assumed the participants would see in their own software. The main question guiding the workshops was: How can we examine the design of the content moderation software through the experiential inputs of the workers while protecting them? With the collective knowledge of our organizing team—including Sana’s academic research on the labor process of content moderation in third-party IT BPO companies in India and Caroline’s design background and expertise in designing digital tools and software—we aimed to answer the research question in a multidisciplinary manner. The practical knowledge of two student assistants at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center further benefited the workshops.

As mentioned earlier, the indispensable aspect of the workshops was their iterative structure; knowledge about the content moderation software was developed gradually, using a step-by-step process wherein participants could build out, think, and iterate on the software design they were recalling. This gave them space to reflect and redraw for accuracy. Each activity started with general questions on the content moderation process, including the generic layout of the software and the moderators’ workflows, which became increasingly specified in the process of adding complexities in each subsequent workshop activity. Much like generating an outline, we could then go more granular, asking about smaller, more specific features and adding more-qualitative questions on the kinds of content they moderated, how their company organized their workday, and how their team used their software. Such a sequential technique allowed the participants to ease into the design thinking process.

The first activity was planned to obtain an undetailed view of the content moderators’ daily workflows and routines. Accordingly, the participants were asked to list the daily sequences of their work. Through this, we could first determine the type of software used, for example, whether or not it was Web-based. Other elements that could be assessed from the participants’ experiences included their observations while logging in to start the moderation work, the first task they undertook after logging in, and the software functions available, including those related to internal communication (e.g., the ability to send emails to management or messages to team members or other coworkers). This overview was important in getting a preliminary grasp on how workers accessed content moderation tasks and whether they were able to exercise flexibility between carrying out work-related tasks and other assignments.

The activity was useful in persuading the participants to revisit their daily work routine and recall the essential elements of their work process. It also gave them a basis for remembering the different kinds of screens and windows in their software.

Building on the first, the second activity allowed the participants to further iterate and lay out the different screens and states of their work software, pulling directly from the initial list they had made. The list helped the participants look back at what each “state” or “screen” held and the kind of actions each screen allowed for.

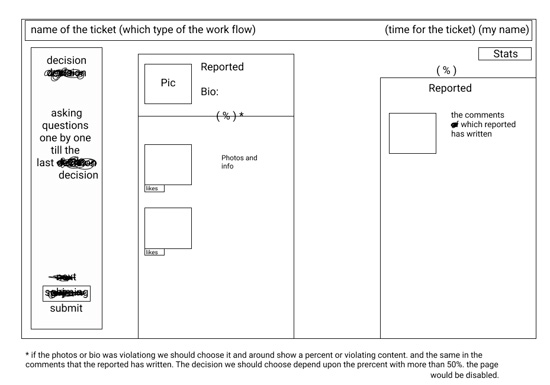

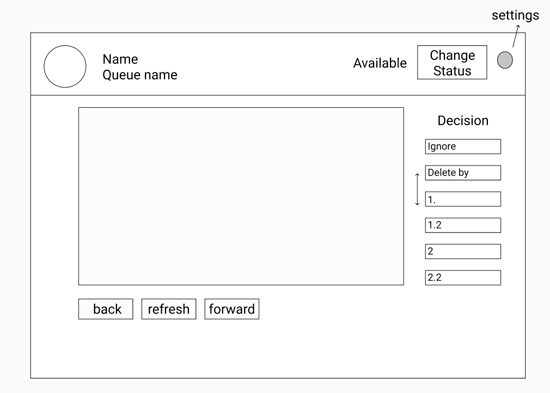

The third exercise was focused specifically on the software page layout and gaining insights into the granular elements. During this activity, the participants started drawing and building out a rough wireframe, with focus placed on elements such as menus and buttons and locating different information in distinct pages and positions in the software. Along with their illustrations, participants also shared with us the experiential narratives of the content moderation process, including the management control embedded in the software. Our questions related to these themes spurred responses from the participants.

Wireframes from activity 3 in the second workshop, where participants detailed the software page layout.

Conclusion

We see the merits of this research method, especially in being able to draw out human-machine interaction through the collective memories of our participants. Our workshops yielded software design layouts, which are unique given the limited information available on the labor processes of social media content moderation. At the same time, conducting a workshop or focus group interviews can be more fruitful when combined with one-on-one interviews. Considering the precarious background of our participants and their limited possibilities for exercising collective struggles against management, we managed to create a space where current and former content moderators were able to share their work-related experiences and management interactions with us and with one another by focusing on the content moderation software. Future research on the use of technical control and novel ways of labor resistance using technology can enrich the existing research on content moderation.

Posted in: on Thu, June 24, 2021 - 10:02:38

Caroline Sinders

View All Caroline Sinders's Posts

Sana Ahmad

View All Sana Ahmad's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found