Authors: Ahmet Börütecene , Oğuz Buruk

Posted: Mon, February 28, 2022 - 12:46:19

How can I tell what I think till I see what I make and do? — Christopher Frayling [1]

Just a couple of months before the start of the new decade and the pandemic began haunting the world, we had the privilege to attend the Halfway to the Future symposium (https://www.halfwaytothefuture.org/2019/) in person and present a paper. The symposium was organized on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Mixed Media Lab at the University of Nottingham. There were many exciting keynotes, presentations, and panels. At that time, we did not know that this would be one of the last physical presentations we would give for a while. In this blog post, we would like to talk about the stage performance we did to present our paper and how it motivated us to open a discussion on alternative ways of communicating scientific knowledge, in particular that which is produced through HCI and design research.

For the symposium, we submitted a provocative paper that envisions using a Ouija Board as a resource for design [2], which was then presented in the session built around the influential work of Bill Gaver on ambiguity [3]. Briefly, the Ouija is a parlor game where participants place their fingers on a physical cursor (planchette) and ask questions to an invisible being—supposedly a spirit. The being moves the cursor—although it is moved unconsciously by humans due to the ideomotor effect [4]—around the letters on the Ouija board to answer the questions. We were excited by how the Ouija mechanism combines ambiguity and human touch in an intriguing way, making it a collective, playful, and evocative medium for ideation. Through its embodied and narrative affordances, the Ouija minimizes verbal communication and focuses participants’ attention on the movement of their hands and the planchette around the letters on the board for a tacit conversation. Using the Ouija was quite experimental for us, and the ambiguity that it embodies was also at the heart of our research process, as we kept discovering new experiences and challenges each time we iterated our Ouija design sessions with different people

When we started thinking about how to present our research, sequential static slides did not look like an ideal way of showing our journey, nor our confusion and excitement about the potential of Ouija for design. Show-and-tell was another alternative. However, although many things can be explained through annotations, the design object, or the object of design, still has a lot more to communicate that cannot be translated into a traditional show-and-tell. In the end, we decided to use the artifact itself to talk about our research. One of the advantages is that our object of research/design had an intrinsic performative aspect and thus could afford a theatrical presence on the stage. We started exploring how to exploit this aspect and use the narrative it could offer.

After playing with the Ouija for a while, we noticed that we did not have to show our real-time interaction with it, but instead could show on a large screen a prerecorded video of us doing the intended actions to make the audience believe that it is actually a live video. This introduced another challenge, though: the requirement to perform on the stage in sync with the prerecorded video. Although challenging, it fit very well the spirit of the symposium: mixed reality. It was a little bit risky, and we did not have much time for rehearsal, but we wanted to give it a shot.

We wrote a vague script for our Ouija performance and started playing along in the hotel room. As we were playing, we were both rehearsing our script and discovering the Ouija board and how to use it for the performance as well as for design. This process not only unfolded the dialogue we intended to create between two people as researchers for presentation purposes, but it also facilitated our dialogue as designers exploring the Ouija board by enabling us to reveal aspects of it that we did not have the chance to notice earlier. So the efforts toward developing a way to communicate our research also became a way to explore the design space further and have a better understanding of it. In the end, the video was ready, and the performance was a success. The audience followed along with the script and caught the key moments clearly.

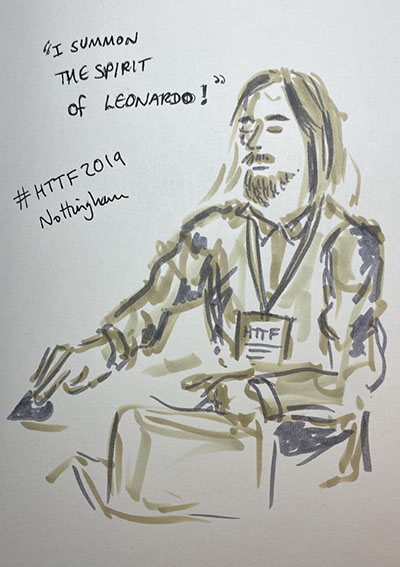

The point, though, is not the success of our presentation. Also, it is not the first performative presentation made for scientific communication, having been preceded by many others. However, we believe that it is worth discussing the generative impact of such presentations not only on the audience, but also on the presenters, design objects, and the research. There may be a certain value in thinking about how an artifact can be the “subject” doing the scientific communication rather than just being the inert “object” frozen during knowledge creation. This approach configures the interaction with the artifact in a way that may help with the challenges in communicating design knowledge and can be complementary to methods such as annotated portfolios. Moreover, we also had the chance to see that such a performance has an intrinsic value for communicating design knowledge that makes an impact on the audience. It not only helped us engage the audience, but it also provoked research ideas and spontaneous action in the hall. For example, one of the presenters in our panel, Miriam Sturdee, did a sketch during the performance (Figure 1), and later Katherine Isbister asked us if we could place our Ouija board at the corner of the stage to receive questions from the audience during the panel she was moderating. It was also nice to see some parallels to our performance at the symposium. For example, Steve Benford used an old slide projection to show the slides he used years ago to present one of his early works presented at CHI, and then went on with a digital presentation.

Figure 1. Sketch made by Miriam Sturdee during the Ouija

performance (used with permission)

Inspired by this experience, we would like to discuss the value of such performances at scientific venues and how they could open up new possibilities to communicate research outcomes as well as to create engagement in different types of audiences. Moreover, we also consider it important to reflect on how such an approach can contribute to authors/designers themselves to have a better understanding of the artifact or topic they are exploring. Instead of thinking of the presentation as a fixed and predictable thing, we might see it as a performance that enables designers, researchers, and audiences to experience the results in the making, as the continuation of a reflective dialogue with the design object. We believe an important aspect of our performance was that it was not a gimmick or special effects. It was a moment where the design object, or the object of design, spoke for itself and this made sense under the symposium theme. Can this kind of approach inspire alternative ways of presenting research processes, disseminating findings, or even reviewing scientific publications? One example toward this direction is the “not paper” [5], which criticizes current publishing formats and practices through its particular embodiment. DIS runs a pictorial track where authors are encouraged to communicate their research through visual-driven papers. Video articles are another example [6]. We would like to hear what design communities have to offer in this direction: Can making multisensory papers be a way of articulating insights addressing different sensory channels, be they haptic, gustatory, auditory, etc.? For example, can we hug or bite the text? Or, why not games as potential presentation formats? Instead of making slides, can we organize a live-action role-playing setting for keynote presentations? How should we go further?

Endnotes

1. Frayling, C. Research in Art and Design. Royal College of Art, London, 1993.

2. Börütecene, A. and Buruk, O. Otherworld: Ouija Board as a resource for design. Proc. of the Halfway to the Future Symposium. ACM, New York, 2019, 1–4; https://doi.org/10.1145/3363384.3363388

3. Gaver, W.W., Beaver, J., and Benford, S. Ambiguity as a resource for design. Proc. of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2003, 233–240; https://doi.org/10.1145/642611.642653

4. Häberle, A., Schütz-Bosbach, S., Laboissière, R., and Prinz, W. Ideomotor action in cooperative and competitive settings. Social Neuroscience 3, 1 (2008), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470910701482205

5. Lindley, J., Sturdee, M., Green, D.P., and Alter, H. This is not a paper: Applying a design research lens to video conferencing, publication formats, eggs… and other things. Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2021, 1–6; https://doi.org/10.1145/3411763.3450372

6. Löwgren, J. The need for video in scientific communication. Interactions 18, 1 (2011), 22–25; https://doi.org/10.1145/1897239.1897246

Posted in: on Mon, February 28, 2022 - 12:46:19

Ahmet Börütecene

View All Ahmet Börütecene 's Posts

Oğuz Buruk

View All Oğuz Buruk's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found