Authors: Steve Benford

Posted: Mon, August 19, 2013 - 12:46:45

I’m just back from a short camping trip and reflecting on how exciting it is to live under canvas. There is a visceral thrill to being in a tent as the thin fabric leaks noise, light, heat, and shadows. Laying awake in the dark you become aware of nearby voices, the sound of rain pattering on the roof, the tent shaking in the breeze. It’s the perfect time to imagine a world of stories that might be happening outside.

Summer camping (there’s rain on the way)

The Storytent

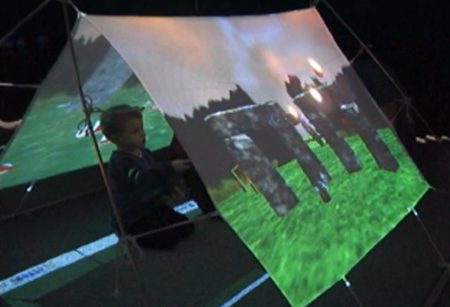

This fascination with tents has inspired several projects at the Mixed Reality Lab. The Storytent aimed to create an intimate and exciting interactive storytelling environment for children. We folded a projection screen into the shape of an A-frame tent and projected synchronized graphics onto both sides, as well as sound, to create a mini immersive environment. We experimented with various ways of interacting with the tent: RFID readers placed at its ends recognized the comings and goings of (tagged) occupants and their possessions; a touch-screen map transported the tent to new locations in the virtual world; while shining flashlights onto the tent manipulated virtual objects as shown in this short video. This final technique used bespoke computer vision software for identifying and tracking flashlight beams.

Using flashlights to interact in the Storytent

We deployed the Storytent at Nottingham Castle, the ancient site of many thrilling and gruesome stories: Richard the Lionheart arrived there to confront King John after crusading (but he spoke French so the locals wouldn’t let him in); Richard III rode out from there to his death at Bosworth Field (they’ve recently dug him up again in nearby Leicester); Charles I raised his standard there to declare the English Civil War and summon an army (but no-one turned up so he went to Oxford instead); the locals burned down the Castle during the Corn Law riots (you may be getting a sense of Nottingham’s attitude to authority by now); and of course, Robin Hood got up to all sorts of adventures there (and yes he absolutely did exist).

Historical digressions aside, what better place to experience these stories—which children did by exploring the castle grounds and filling in paper clues (which were tagged with RFID) before taking them into the Storytent and using them to trigger the replay of stories.

ExoBuilding

If the Storytent strives for excitement, then our second interactive tent aims for the opposite: meditative relaxation. ExoBuilding has been created by Holger Schnädelbach, Alex Irune, Dave Kirk, Kevin Glover, and Patrick Brundell as an early prototype of a built structure that reacts physically to its occupants’ activities—an idea that they call adaptive architecture.

Exobuilding takes the form of a tent that flexes and moves in direct response to an occupant’s respiration while also sonifying their heartbeat. Early experiments revealed that this form of biofeedback triggers changes in participants’ physiology, leading to lower respiration rates and higher respiration amplitudes, respiration to heart rate coherence and lower frequency heart rate variability, and causing some people to report feeling more relaxed. The team suggests that there is potential for use as a biofeedback device.

ExoBuilding flexes in response to breathing

Tents as interfaces

These tents have some distinctive and unusual properties when considered as computer interfaces.

They surround and enclose their occupants to form an immersive display, similar in principle to a virtual reality CAVE, but very different in practice due to their personal scale. Of course, it can be tricky to read high-resolution graphics on a screen that is so close to your eyes, or to move, gesture, and look around in order to interact when sitting in a cramped tent. On the other hand, the snugness of the tent lends a sense of intimacy to storytelling, while isolation may help with relaxation. Also, not being able to turn or look around quickly can bring suspense to storytelling, emphasizing the feeling that something may be approaching from behind.

Unlike larger immersive displays, tents have both insides and outsides. This allows for a separation between those who are immersed and interacting inside, for example a child engaging with a story, and a wider audience that remains outside the tent but can still see what is happening, for example parents or perhaps other children who are waiting for a turn. A tent is therefore an example of a spectator interface, an interface that is deliberately designed to reveal some, although not all, aspects of interaction to an audience.

As with the fabric of a regular tent, the screens of our interactive tents are porous membranes, leaking sound and light in both directions. This opens up opportunities for playful interactions between those inside and those outside, such as whispering, casting shadows, and even shaking the tent (great fun for parents!).

Finally, as the Exobuilding shows, they can flex and move, changing shape and form under computer control, introducing a sense of physicality and even synchronizing with an occupant’s physiological responses.

Interfaces as tents?

In turn, these interactive tents illustrate a wider interaction design principle. Might it be useful to think of all interfaces as being “tents,” by which I mean as permeable boundaries that connect different worlds or spaces. My colleague Boriana Koleva first explored this idea during her PhD research and referred to such interfaces as “mixed reality boundaries.”

So the Storytent is a permeable boundary that connects three spaces: the physical spaces of inside and outside and a virtual world. It both separates these spaces, providing a degree of isolation and intimacy, but also allows some information and interactions to flow between them, even including participants who can traverse the boundary, for example entering tent from the outside or entering the virtual world.

Is it useful to conceive of other interfaces as being tent-like permeable boundaries? Might games consoles be designed around the idea that players peer into or enter a virtual world while others look back out at them (especially now they routinely come equipped with cameras such as the Kinect)? Should communication tools such as Skype be reimagined as boundaries between physical spaces that might afford different kinds of isolation and permeability? Might even the familiar web browser be reconceived as a permeable boundary to the Web, one through which we look while others look back out at us, tracking our movements and actions?

There may be something to be said for seeing these interfaces as permeable membranes, encouraging us to reflect on how information, interaction, and presence flow both in both directions and how we might want to design this to enable or restrict such flows, address audiences as well as users, or simply to lend them some tent-like excitement. Perhaps we are all interacting under canvas after all?

Posted in: on Mon, August 19, 2013 - 12:46:45

Steve Benford

View All Steve Benford's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found