Authors:

Posted: Tue, January 10, 2017 - 10:38:04

Shortly before the widespread availability of photographs in the first third of the 19th century, stereoscopes appeared. We’ve been flirting with portable, on-demand three-dimensionality in experience ever since.

From Sir Charles Wheatstone’s invention in 1838 of a dual display to approximate binocular depth perception through the ViewMaster fad of the 1960s, people have been captivated by the promise of a portable world. Viewing two-dimensional images never seemed enough; yet to view a three-dimensional image of Confederate dead at Gettysburg or of a college campus helped bring people into connection with something more real.

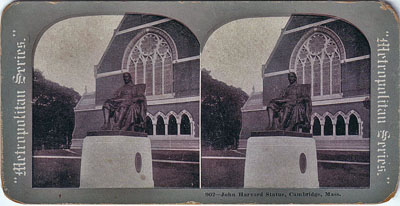

This image of the original John Harvard statue shows what a

typical stereoscope card looked like.

Lately I’ve been experimenting with Microsoft’s HoloLens, an augmented reality (AR) headset that connects to the Internet and hosts standalone content.

Similar to other wearables such as Google’s now-defunct Glass, HoloLens requires the user to place a device on their head that uses lenses to display content. As an AR device, it also allows the user to maintain environmental awareness—something that virtual reality (VR) devices don’t.

Many other folks have written reviews of these devices; that’s not my purpose here. Instead, I’ve been thinking about the interaction promises and pitfalls that accompany AR devices. I’ll use the HoloLens as my platform of discussion.

The key issue for interaction in AR center around discoverability, context, and human factors. You have to know what to do before you can do it, which means having a conceptual model that matches your mental model. You need an environment that takes your context into consideration. And you need to have human factors such as visual acuity, motor functions, speech, and motion taken into account.

Discoverability

We talk of affordances, those psychological triggers that impart enablement of action. Within an augmented world, however, we need to indicate more than just a mimicked world.

Once the device sits on a user's head, the few hardware buttons on the band enable on/off and audio up/down. Because the device is quick to turn on or wake from sleep, it provides quick feedback to the user. This critical moment between invocation of an action and the action itself becomes hypercritical in the augmented world. Enablement needs to appear rapidly.

For HoloLens users, the tutorial appears the first time a user turns the unit on. It's easy to invoke it afterwards as well. Yet there's still a need for an in-view image that enables discoverability.

Context

Knowing where you are within the context of the world is critical to meaning. As we understand from J.J. Gibson, cognition is more than a brain stimulation: It's also a result of physical, meatspace engagement.

So a designer of an AR system must understand the context in which the user engages with that system. Mapping the environment helps from a digital standpoint, but awareness of objects in the space could be clearer. Users need to know the proximity of objects or dangers, so they don't fall down stairs or knock glasses of water onto the floor.

Human Factors

Within AR systems, the ability to engage physically, aurally, and vocally entails a key understanding of human factors. Designers need to show concern for how much physicality the user needs to engage with.

In the HoloLens, users manipulate objects with a pinch, a grab, and a "bloom"—an upraised closed palm that then becomes an open hand. A short session with HoloLens is comfortable; too much interaction in the air can get tiring.

Voice interfaces litter our landscape, from Siri to Alexa to Cortana. HoloLens users can invoke actions through voice by initiating a command with "Hey, Cortana." They can also engage with an interface object by saying "Select."

Yet too often these designed interfaces smack of marketing- and development-led initiatives that don't take context, discoverability, or human factors into account. The recent movie Passengers mocks the voice interfaces a little, in scenes where the disembodied intelligence doesn't understand the query.

We've all had similar issues with interactive voice response (IVR) systems. I'm not going to delve into IVR issues, but AR systems that rely on voice response need to take human factors of voice (or lack thereof) into account. A dedicated device such as the HoloLens seems to be more forgiving of background noise than other devices, but UX designers need to understand how the strain of accurate voicing can impact the user's experience.

Back to Basics

User experience designers working on AR need to understand these core basic tenets:

- Factor in discoverability of actions into a new interaction space.

- Understand the context of use, to include safety and potential annoyance of neighbors to the user.

- Account for basic human factors such as motor functions, eye strain, and vocal fatigue.

Posted in: on Tue, January 10, 2017 - 10:38:04

Post Comment

No Comments Found