Authors: Steve Benford

Posted: Mon, October 07, 2013 - 10:22:03

Why is the Imperial War Museum North like Oblivion, the world’s first vertical drop rollercoaster? Sounds like the beginning of bad joke doesn’t it? But actually they do have something significant in common. Moreover, it’s something that speaks to how we interact with computers.

Which is which?

The answer is that both have been deliberately designed to make people uncomfortable. This is perhaps rather obvious with Oblivion, which sets out to terrify its victims from the start, warning them that it’s not too late to turn back as they queue, slowly cranking them up a steep incline, pausing them on the brink of a terrifying drop for several seconds as they listen to the instruction “don’t look down,” before then plunging them into a dark tunnel 60 meters below. The discomfort is more subtle in the Imperial War Museum North, but it is ever present all the same, as Daniel Libeskind’s award-winning building features sloping floors and ceilings throughout so as to induce the kind of disorientation experienced in war. Of course, Oblivion and IWMN, as it is known, employ discomfort for quite different reasons. With the former, it is an essential ingredient of the entertainment. With the latter, the aim is to frame an appropriate engagement with challenging material as part of an enlightening visit.

Why on earth?

It has been exciting this month to see the publication of our article “Uncomfortable User Experience” as the cover feature of September’s Communications of the ACM. In this article we make a case for the deliberate use of discomfort in interaction design. This is a somewhat unusual position, as the principles of interaction design traditionally emphasize providing the user with the most comfortable experience possible, one where they are in control rather than being taken for a ride, and where they remain oriented rather than being deliberately disoriented.

However, as computers increasingly find their way into cultural experiences—from highbrow arts and museum visits to mainstream entertainment such as games and rides—so new design principles emerge. As with Oblivion, discomfort may support the goal of entertainment, or as with the IWMN may serve the purpose of enlightenment. We also discuss a third motivation for introducing discomfort, that of social bonding, where a shared rite of passage brings people together.

The deliberate use of discomfort has long been practiced in fields outside of computing, most notably in the performing arts, where there is an established tradition of inviting audiences to witness uncomfortable spectacles, or even become implicated or directly engaged in them. This tradition has spilled over into human-computer interaction as it has engaged with the performing arts. Our article explores two examples of this.

Blast Theory’s Ulrike and Eamon Compliant invites participants to enter the world of a terrorist as they undertake a guided city walk. The artists demand increasing compliance with instructions before ending with a face-to-face interrogation conducted by an actor. As you leave the room, you get to look back through a one-way mirror to briefly spy on the next person being interviewed.

The interview in Ulrike and Eamon Compliant

In contrast, Brendan Walker’s breath-controlled amusement ride Breathless creates an intimate and viscerally uncomfortable connection between a human and a robotic ride in which riders wear rubberized gas masks equipped with breathing sensors and witness and even control each others’ experiences.

Breathless

Four forms of discomfort

Such experiences may appear to be far removed from the mainstream, but they do serve to powerfully illustrate some of the ways in which discomfort can be introduced into interaction design. Indeed, they have led us to identify four broad forms of discomfort along with various tactics for deploying them.

Visceral discomfort focuses on physical sensation, involving tactics such as designing unpleasant wearables (such as Brendan’s gasmasks) and tangibles. It encourages strenuous physicality (here one thinks of Floyd Mueller’s exertion games) or even causes pain.

Cultural discomfort, in contrast, invokes dark thematic associations or confronts difficult decisions (such as in Ulrike and Eamon Compliant and IWMN).

While these are certainly relevant to interaction design, our second two forms of discomfort lie right at its heart. One of Ben Shneiderman’s famous Eight Golden Rules of interaction design is to “support internal locus of control,” which means keeping the user in the driving seat as long as possible. One way of creating discomfort in interaction is therefore to have the system take control, as is the case with Blast Theory’s demanding instructions, and pretty much any rollercoaster you can name where the rider is helplessly strapped in for the duration of the ride. Design tactics here include surrendering control to the machine, surrendering control to other people, and in a reversal of these, requiring participants to take an unusually high degree of control or responsibility.

Our last form of discomfort concerns intimacy. Computers are increasingly mediating our social experiences which gives rise to the possibility of distorting normal social relations in uncomfortable ways, for example isolating people (used in both Breathless and Ulrike and Eamon Compliant), employing surveillance and voyeurism (also used in both), and establishing unusual intimacy with strangers. An intriguing example of the latter is to be found in Mads Hobye’s and Jonas Löwgren’s account of the performance Mediated Body, in which members of the public touch a performer’s body in order to explore an interactive soundscape.

Remember the point

Having told you how to create uncomfortable interactions, now is a good time to pause for a moment and reflect again on possible motivations. The ultimate aim here is to employ discomfort in the service of a greater goal—enlightenment, entertainment, or social bonding. This means that uncomfortable interactions need to be very carefully embedded into a wider experience in such a way that they are properly resolved.

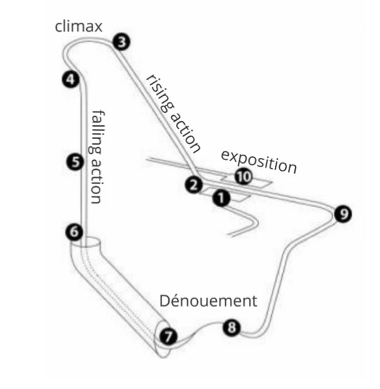

Again, we can turn to the world of theatre for inspiration. The Renaissance saw the development of the classic five-act performance structure known as Freytag’s pyramid, consisting of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and finally dénouement. Personally, I can see a striking resemblance between this pyramid and the design of Oblivion.

Oblivion as Freytag’s pyramid

It seems that rollercoaster designers may understand performance structure, and invest effort into designing an entire trajectory through discomfort rather than just an uncomfortable experience per se.

With this in mind, there are some forms of discomfort that are more problematic. While the uncomfortable suspense of the slowly rising action on Oblivion is part of the entertainment, I find other rides to be uncomfortable because they make me nauseous, a sensation that is not quickly resolved during the ride and that lingers some time afterwards. I certainly wouldn’t encourage you to design experiences that induce nausea as a form of discomfort (and here I include those of you working with virtual reality head-mounted displays, which seem to be making something of a comeback right now).

Can this be ethical?

You—as a prospective designer of uncomfortable interactions—are also going to need to carefully consider ethics. Adopting a consequentialist approach as proposed by Jeremy Bentham, you need to consider whether the ends justify the means. Do the benefits of enlightenment, entertainment, or social bonding for the individuals involved justify any temporary and properly resolved discomfort? In short, with hindsight, would you participants be happy with what has occurred?

There are other ethical issues to negotiate too. What does informed consent mean in an experience that deliberately contains shocks and surprises? Where is the right to withdraw from a rollercoaster once it is underway? What of privacy in experiences that employ voyeurism? Again, interaction designers are going to need to learn from the world of theatre where performers have an established tradition of negotiating the boundaries of ethical behavior with their audiences, both during and within performances, though certainly not always without controversy.

A shocking experience

So I’m suggesting that interaction design needs to take a considered view of the idea of deliberately designing uncomfortable interactions. They are clearly part of the repertoire of cultural experiences, from performances and museum visits to games and rides. I suspect that there may be interesting resonances with other application domains too. I wonder, for example, whether we can apply any of these ideas to the design of health journeys? How could we deliberately redesign a visit to the dentist if we thought of it as a trajectory through discomfort?

A shocking game

I’ll close this post with a shock. Quite literally. Earlier on I mentioned causing pain as a form discomfort. This would seem to be quite an extreme idea (and indeed it is, and should be treated with great caution). This said, I recently treated myself to an electric shock reaction time game for less than twenty bucks. It gives a nasty jolt and therefore induces a high degree of suspense. I’m not sure that it’s that entertaining personally, but its glowering presence in the centre of my table certainly adds an extra frisson to student supervisions.

Posted in: on Mon, October 07, 2013 - 10:22:03

Steve Benford

View All Steve Benford's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found